Colonial Christmas

This Christmas season, many of us celebrate with traditions passed down from our parents and grandparents. Some of us have made new traditions to celebrate Christmas. Do we ever consider where these traditions originated? Some traditions have changed over the years. For our ancestors in colonial America, Christmas looked different for them than it does for us today. Perhaps some of these traditions are worth reviving and adding to our current traditions. Let’s take a look at some of these traditions.

Notable Christmases in American history

Christopher Columbus landed in the Americas in October 1492 and was still there at Christmastime. On Christmas day, one of his ships went aground, and Columbus saw that as a sign from God that he should settle in this new land. So, he and his men used the timbers from the ship to build a fort and called it Villa de la Navidad—Town of the Nativity. This settlement failed, but others followed.[1]

One of these later settlements was Jamestown in 1607. This settlement struggled; only thirty-eight of the original 100 settlers were still alive in winter and they were ready to abandon the colony. Despite these bleak conditions, they held a simple Christmas service. Relief vessels were on their way, allowing the colony to grow and thrive.[2]

Shortly after that, the Pilgrims settled Plymouth colony. Christmas of 1620 was just another work day for them. The following year, some wished to make merry. Governor Bradford was against reveling in the streets but was okay with private devotions in the home.[3]

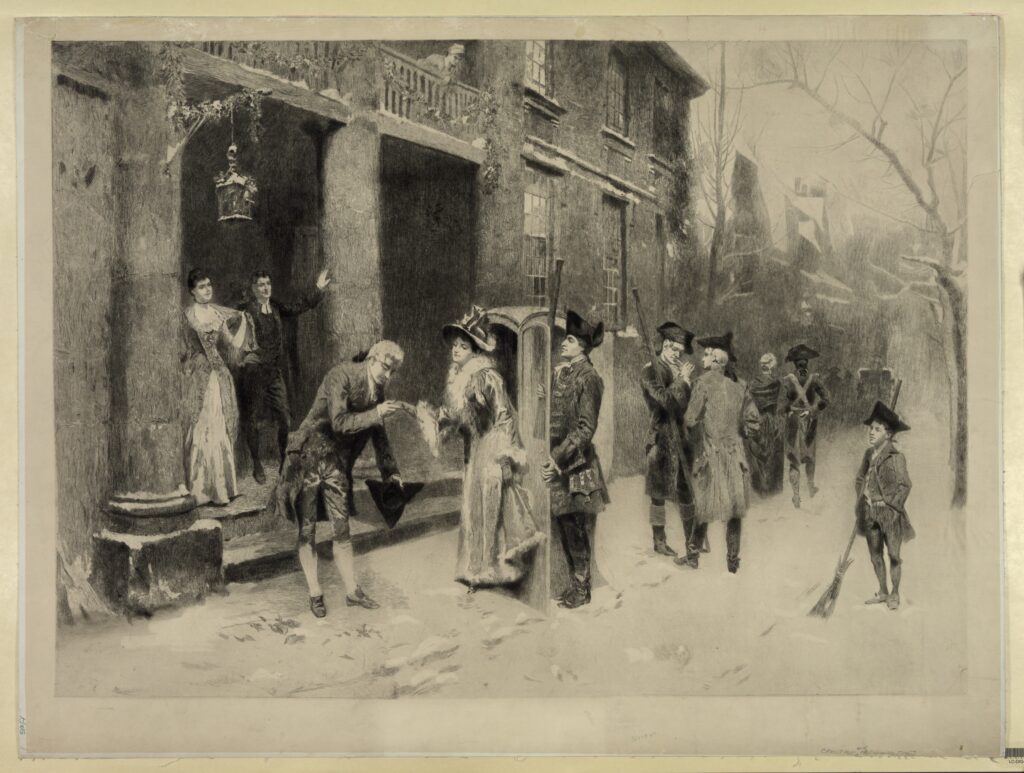

Christmas of 1776 was more epic. This was during the Revolutionary War. Earlier that year, George Washington’s poorly trained troops had been beaten by a 15,000-man British army. Washington’s army was being depleted—some men who did not get killed or captured deserted the army. Many had only signed up to serve until the end of the year, meaning Washington would have to find replacements. Things were not looking good for Washington and his army, especially if they got defeated again. The British army set up winter quarters rather than launching an attack, so Washington decided to lead his men on the offensive. On Christmas night, he led his men in boats across the river during a snowstorm to launch a surprise attack on the British. This was devastating to the British army. This victory boosted the morale of Washington’s army and was a turning point in the Revolutionary War. What better Christmas present could Washington have given to America?[4][i]

Christmas in the north

Christmas was less celebrated in the North than in the South because the religiously prominent in the North were against Christmas festivities. These people included Puritans, Baptists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Quakers.[5] Considering the Christmases in days olden to them, it is no wonder that conservative Christians would have been against the celebrations. The Christmases of medieval times included reveling and doing illegal activities, some stemming from ancient pagan traditions. Even when early Christian leadership declared December 25th as Christ’s birthday, many Christians chose to party in the pagan style and then repent later.[6]

Puritans’ argument against Christmas was that it wasn’t mentioned in the Bible. They were also against other holidays for the same reason. Cotton Mather, a Puritan clergyman, argued that the mad mirth, long eating, hard drinking, lewd gaming, and rude reveling did not honor the Savior.[7]

Quakers’ argument against Christmas was similar to that of the Puritans about it not being mentioned in the Bible. A Quaker newspaper author of 1788 even quoted Bible verses against setting one day apart as holy. The Quakers believed Christ should be remembered continually rather than one day a year.[8]

Christmas was made illegal in Massachusetts Bay Colony for a while. It was outlawed in 1659, and anyone caught celebrating was fined five shillings. Even mince pies had been outlawed. This law was repealed in 1681, but Puritan clergymen continued to preach about how Christmas was immoral.[9]

Eventually, the northern colonists softened up on Christmas. Christmas carols, which had been discouraged by some churches,[10] could be heard in the northern colonies as early as 1759. The colonists up north did not find the alcoholic wassail proper, but they decided it wasn’t sinful to eat mince pie or to decorate their homes with a bit of holly. Even when the Northerners began celebrating Christmas, it was nothing compared to the Southerners’ way of celebrating.[11]

Christmas in the south

Religious freedom was less strong a pull to the Southern colonies than in the North. Additionally, religions that approved of Christmas were more prominent, such as Anglicans, Episcopalians, Dutch Reformed, Lutherans, and Roman Catholics.[12] These colonists brought their traditions from the old country and started several of their own.[13]

In Virginia, the entire Christmas season was a time of celebration. Great homes opened to all, and guests came and went as they pleased. Hostesses did not bother with invitations and never knew how many guests they’d accommodate for dinners or overnight stays. The parties included music, dancing, and games. They were held often at night until nearly dawn.[14]

Men often went hunting during the day. Houses were decorated with holly, fir, and mistletoe. A Yule log was burned, and many believed it would bring good luck to the household the following year. Any religious services were brief. [15]

Affluent landowners were expected to be generous during the Christmas season, both to their tenants and to the poor. They also gave Christmas presents to their slaves and servants. (Giving gifts to children became common much later.) Servants and enslaved people who were not needed for the holiday parties were sometimes given the season off.[16]

Christmas Day began with a uniquely American tradition that spread throughout the South: making a loud bang. Men would fire their muskets and set off firecrackers and cannons. Those with nothing else would clatter pots and pans from the kitchen.[17]

Christmas dinner was another major event in the South. This meal would include up to seven or eight courses, which included turtle soup, oysters, crab, codfish, roast beef, Yorkshire pudding, venison, boiled mutton, suckling pig, hickory smoked ham, roast turkey with stuffing, at least five vegetables, hot biscuits, cornbread, and a variety of relishes. The dessert included pies, tarts, puddings, cakes, ice cream, and fruit. Dishes of nuts, raisins, and candy were also served. Wassail and eggnog were common beverages.[18]

Other European influences

The traditions discussed so far were of English influence. People from other European countries also migrated to the English colonies, which later became the USA. The traditions they brought with them included their own ways of celebrating Christmas.

New York was initially a Dutch colony and had been called New Amsterdam. A Dutch Christmas tradition brought from Holland was children leaving their wooden shoes by the fireplace so Sinterklaas could put gifts in them. Good children received small presents, cakes, and candies, while naughty children received switches. The Dutch also had their Christmas parties and feasts like the English settlers of Virginia.[19]

The Christmas tree tradition originated in Germany, and Germans brought that tradition with them when they settled in Pennsylvania. They also brought the tradition of KristKindlien—German for Christ Child, who would leave gifts for children, much like the Dutch Sinterklaas. KristKindlien eventually evolved into Kriss Kringle.[20]

Moravians, who also immigrated from Germany, kept simple Christmas celebrations. They held a love feast and celebrated with scripture, music, and lighting candles. Their love feast included buns, coffee, and a Christmas cookie called Lubkucken. A recipe is given below.Another tradition they brought was their extensive version of the manger scene.[21]

Moravian Christmas cookies[22]

- ¼ cup lard

- ¼ cup butter

- 1 cup molasses

- ½ cup firmly packed brown sugar

- 1 teaspoon cinnamon

- 1 teaspoon cloves

- ¾ teaspoon ginger

- ¾ teaspoon baking soda

- 3 ½ cups flour

Melt land and butter together. Set aside to cool. Mix molasses and brown sugar in a bowl. Add melted fat and mix well. Blend spices, baking soda, and one tablespoon of flour; stir into molasses mixture. Add the remaining flour—Refrigerate the dough for at least 4 hours. Roll out the dough very thin on a floured surface. Cut into shapes and lay on creased cooky sheets. Bate at 350 degrees Fahrenheit for 8 to 10 minutes.

How did your ancestors celebrate Christmas? What old traditions do you want to reintroduce to your family? Lineages can help you learn more about your recent and long-ago ancestors.

Katie

[1] Chicago World Book Encyclopedia, Inc. (1975). Christmas in the Colonies. In Christmas in colonial and early America. An essay.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Gulevich, T., & Stavros-Lanning, M. A. (2000). America, Christmas in Colonial. In Encyclopedia of Christmas: Nearly 200 alphabetically arranged entries covering all aspects of Christmas, including folk customs, religious observances, history, legends, symbols, and related days from Europe, America, and around the world. essay, Omnigraphics.

[6] Collins, A. (2003). Stories behind the great traditions of christmas. Zondervan.

[7] Chicago World Book Encyclopedia, Inc. (1975). Christmas in the Colonies. In Christmas in colonial and early America. An essay.

[8] “The Quakers Reasons for not Observing Christmas Day,” The American Herald and the Worcester Recorder (Worcester, MA), 20 November 1788, 3; digital images, GenealogyBank (https://genealogybank.com: 13 December 2023).

[9] Chicago World Book Encyclopedia, Inc. (1975). Christmas in the Colonies. In Christmas in colonial and early America. An essay.

[10] Omnigraphics. (2000). Christmas Carol. In Encyclopedia of Christmas: Nearly 200 alphabetically arranged entries covering all aspects of Christmas, including folk customs, religious observances, history, legends, symbols, and related days from Europe, America, and around the world: Suppllemented by a bibliography, and lists of Christmas web sites and associations, as well as an index. essay.

[11] Chicago World Book Encyclopedia, Inc. (1975). Christmas in the Colonies. In Christmas in colonial and early America. essay.

[12] Gulevich, T., & Stavros-Lanning, M. A. (2000). America, Christmas in Colonial. In Encyclopedia of Christmas: Nearly 200 alphabetically arranged entries covering all aspects of Christmas, including folk customs, religious observances, history, legends, symbols, and related days from Europe, America, and around the world. essay, Omnigraphics.

[13] Chicago World Book Encyclopedia, Inc. (1975). Christmas in the Colonies. In Christmas in colonial and early America. An essay.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Chicago World Book Encyclopedia, Inc. (1975a). Christmas Dinner. In Christmas in colonial and early America (p. 73). essay.

[i] All images are public domain.