Upper South United States Genealogy Research

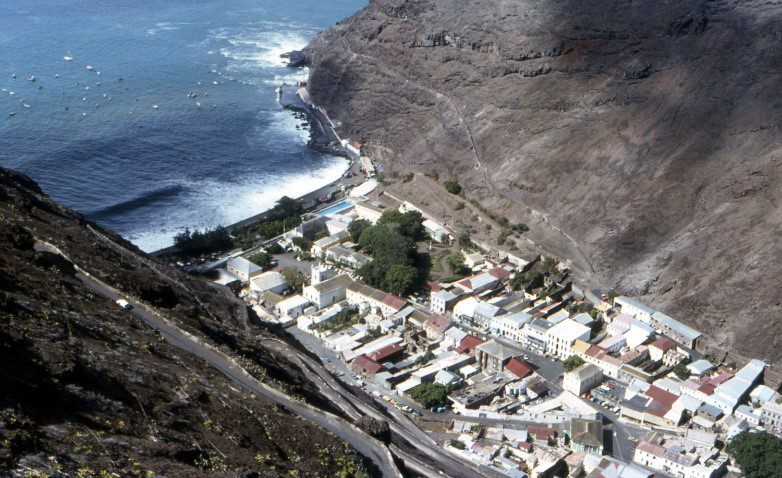

Americans today, whose ancestors lived in the early Virginia and Carolina colonies, are connected to some of our nation’s most significant historical events. They were Native Americans; they migrated from Europe and settled in Jamestown and elsewhere; they came as colonists and indentured servants; they arrived as captured Africans in 1619 and before; they went to battle on both sides of the Revolutionary War; they fought in the Civil War; people of different backgrounds who wove a tapestry of the diverse America that we know today. From Virginia and North Carolina came Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia. If you have ancestors from any of those five states of the Upper South, this article is for you.

History

Virginia and North Carolina were claimed by the English in the sixteenth century, and the first successful settlements were in the early seventeenth century. The prior habitation of tens of thousands of Native Americans did not deter the Europeans for very long.

Virginia Colony granted land to free settlers. The “headright system†gave fifty acres of land to anyone who paid his own way to Virginia, and an additional fifty acres for each person for whom they paid passage. This attracted thousands of settlers.

In 1619, a Dutch trader from the West Indies brought captured people from Africa. Due to an ever-present need for laborers, slavery become more codified by the 1660s. The legacy of slavery continues to the present day.

North Carolina was initially settled by Virginians in 1650. Thirteen years later, the king granted the Carolina colonies to eight Lords Proprietor. The proprietorship lasted until 1729 and settlement increased after that. Because North Carolina’s stormy coast lacked a natural port, most migration there was overland.

The Cumberland Gap, which is situated where the west corner of Virginia meets Tennessee and Kentucky, had been a major migration passage from Virginia to what would become Tennessee and Kentucky. Migrants included Scotch Irish and Germans from Pennsylvania.

The lands that are now Tennessee and West Virginia were Native American hunting grounds and places of inter-tribal competition. The earliest European explorers to Tennessee came in during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The earliest European settlement was in 1756/1757. North Carolina claimed part of this land and organized counties there.

North Carolina ceded its western lands to the federal government. Those lands became the Territory South of the Ohio River or the Southwest Territory, then later became the state of Tennessee. North Carolina granted bounty land in Tennessee to Revolutionary War veterans.

Settlement in western Virginia was encouraged as early as 1660, but multiple factors made settlement difficult: mountain barriers, resistance from indigenous peoples, and conflicting English and French claims. Settlement was in earnest by 1730. Settlers, mainly of German descent, came from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and other parts of Virginia.

Kentucky had been part of Augusta County, Virginia, then part of Fincastle County. The first permanent settlements were established in 1774. Settlers after the Revolution included veterans from Virginia claiming bounty land. Settlers also came from the other Upper South states and from the Mid-Atlantic. Because Virginia ignored the Kentucky settlements during the Revolution, Kentucky separated itself from Virginia and become its own state.

Kentucky and Tennessee had a border dispute which lasted until 1820. The surveyors drew the line too far north, and this incorrect border was accepted until 1859 when it was resurveyed. Meanwhile, the families in the border counties of both states didn’t know whether they were in Tennessee or Kentucky, so records of them could be in both states.

Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee seceded from the United States at the beginning of the Civil War. North Carolina sent the most soldiers to fight for the Confederacy. West Virginia broke off from Virginia due to differences over the slavery issue and was admitted as its own state in the United States in 1863. Tennessee and Kentucky were mixed. Men from western and middle Tennessee fought for the Confederacy while men in eastern Tennessee fought for the Union. Kentucky, whose peoples were both for and against slavery, followed a balancing act. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, it was easier for Kentucky to remain in the Union, but as a state where slavery was still legal, Confederates often acted as though it was on their side. After the Civil War, some African Americans migrated north, including into West Virginia.

Upper South United States Records and Research

Census records are a good place to begin research, especially after 1850. Even though Virginia and North Carolina were states by 1790 and enumerated in that census, many of those returns do not survive. This is also the case for Virginia for the 1800 census. Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee all appear on the 1810 census, but some counties are missing. West Virginia appears as its own state in the 1870 census. Before then, residents of that area were enumerated with Virginia on the censuses. North Carolina took state censuses in the eighteenth century. Virginia took colonial censuses.

Another good record type is cemetery records, both the tombstones themselves and the burial records. Family members were usually buried near each other in the same cemetery, near where they lived or died. The burial records or sexton records may contain more information than the gravestones themselves. These records usually include birth and death information, and clues about military service or organizations the ancestor was in. Many gravestone images can be found online at Find-A-Grave or BillionGraves. Historical and genealogical societies often have transcriptions of gravestones in their local area.

Tax, land, and probate records are also good resources, especially before censuses were taken. These records all give information on residency and clues on relationships.

Appearances and disappearances from tax records can be used to infer when a man was born and died, and if he moved. Land records may indicate relationships. Fathers may have given land to sons and sons-in-law; families that bought and sold land with each other often intermarried.

Probate records give the location and date of estate actions and give names of heirs and tell how they are related to each other. For ancestors who died intestate (without a will), there are administrator bonds, inventories, and settlement records. For ancestors who died testate (with a will), there are executer bonds, wills, codicils, and settlement records. If a man died leaving behind minor dependents, there would also be guardianship records.

Search for tax records at town, county, and state level since taxes can be levied at any jurisdiction level. When searching land records, begin with indexes, which will point the way to deeds, mortgages, plat books, grants, warrants, patents, and surveys. Due to the boundary changes and border disputes in the Upper South, it may be necessary to check multiple jurisdictions for your ancestors’ land, tax, and probate records.

To find resources to search tax, land, and probate records, go to the RedBook online, select the state of interest from the list, then select the record type from the menu on the right. Here you will find historical information about records in your chosen state as well as resources to search for these records.

If your ancestors served in a war, military records are a good source of information. This includes the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Civil War, and World War I and II. Bounty land was granted to veterans of the Revolutionary War. Your veteran ancestor, his widow, or any of his dependents may have applied for a pension. Whether or not it was granted, the application process would have left a paper trail containing information about your ancestors. For Civil War veterans, Union soldiers would have applied for a pension through the Federal government, while Confederate soldiers would have applied through their state. Military records can be searched at Fold3. Details of historical context and other resources can be found through the FamilySearch Wiki.

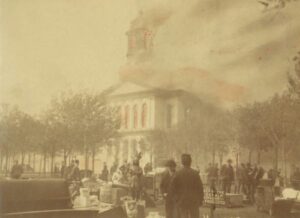

Burned courthouses

The South is notorious for burned courthouses. While many courthouses were destroyed in the Civil War, many were also destroyed by natural disasters such as hurricanes, tornados, and floods. Often the destruction of a courthouse meant the destruction of the records it housed. Sometimes only part of the courthouse was destroyed. Some records within were rescued, so a burned courthouse does not necessarily mean all the records were destroyed.

The county pages within the FamilySearch Wiki will state if a county suffered destruction of a courthouse and will usually state the date and nature of the disaster, as well as the scope of the record loss. When dealing with a burned county, it is more important than ever to meticulously document your research, keep track of where the family lived, and keep track of their associations. This information will be helpful in finding records despite the record loss.

If the county had multiple courthouses, search for records in another courthouse. Also search for records of the family in neighboring counties and at different jurisdiction levels such as town and state records.

Here are some record types to keep in mind when researching burned counties:

- Land records were so important they were often recreated or rerecorded after a courthouse disaster.

- Death records are the only record type that cover events from one’s entire lifespan, and a lot of records were created around an ancestor’s death.

- Local histories and biographies may have information about your ancestors or their associates. These may have been based on sources that were not destroyed.

- Tax records, if they were not stored at the courthouse that burned, can give information on ancestors.

- Newspapers were likely to survive a disaster because a copy would be somewhere away from the disaster.

African American Research

Kentucky was a state where slavery was legal, but it remained loyal to the Union. There were Underground Railroad stations there. In West Virginia, freeing the slaves was a condition of statehood when it asked to join the Union.

African American genealogy can be challenging, even more so before emancipation. Enslaved African Americans were viewed as property by their owners and recorded as such. Slave sales separated African Americans from their families, and these families sought to be reunited after emancipation.

State and Federal Censuses taken after the Civil War list African Americans by name. The 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedules of the U.S. Census only listed enslaved people by gender and age. The enslavers’ names are given, which is very important information.

The Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company was created during Reconstruction to assist newly freed African Americans. The records they created contained information about the person and their family, and sometimes information about the former owner.

To research enslaved African Americans, it is important to know the name of the slave owner, and to research records that could name their slaves. Helpful records to search include wills, estate records, biographies, land records, property sales, journals, local histories, and newspapers.

For additional information on researching African American ancestors, please see this FamilySearch wiki article and our previous blog posts on African American research.

If you need help researching your Upper South Ancestors, Price Genealogy can help.

by Katie

Resources: https://wiki.rootsweb.com/wiki/index.php/Main_Page

Photo 1 “File:St-Helena-Jamestown-from-above.jpg” by Andrew Neaum is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Photo 2 “Civil War veteran Joshua John Casey (B. Dec. 14, 1835 D. Oct. 20, 1902) and Ellen Ham-Casey. (B. May 8, 1851 D. June 8, 1905)” by David C. Foster is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Photo 3 “First courthouse 1891” by Eridony (Instagram: eridony_prime) is licensed under CC BY 2.0