Black History Month! Let’s Explore African American Genealogy

Black History Month is a time of reflection, education, and celebration—a month dedicated to honoring the rich history, achievements, and resilience of African Americans. While we often look to well-known historical figures and major events, one of the most meaningful ways to connect with Black history is by tracing our own family stories. Understanding where we come from is a powerful way to honor our ancestors and preserve the legacy of those who came before us.

For many African Americans, genealogy research presents unique challenges due to historical obstacles such as slavery, migration patterns, and limited documentation. However, with the right tools and resources, uncovering your family history is not only possible but deeply rewarding. In this guide, we’ll explore the basics of African American genealogy, offering tips and insights to help you start your journey toward discovering your roots.

Whether you’re new to genealogy or looking to expand your research, Black History Month is the perfect time to dive into your family’s past and celebrate the stories that make up our collective history.

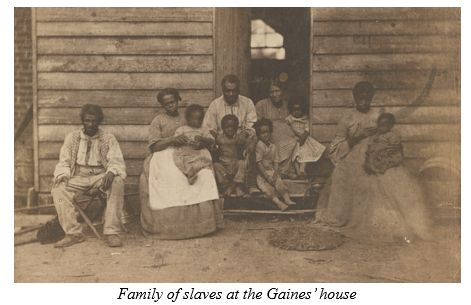

Just before the Civil War started in 1861, United States census takers counted around four million Black children, women, and men enslaved in the United States. During US slavery, there were few good systems in place to record the names and vital information of enslaved people. The federal census did not record the names of enslaved people, just number, sex, color, and age. If the names of enslaved people were ever recorded in a lasting way, it was often only by first name in property records.

Due to this lack of consistent record-keeping, many enslaved people cannot be found by name in any existing record. However, despite the difficulties of researching enslaved people, there are often more records than descendants expect.

Currently, more than forty million US residents identify as Black American. Six out of ten Black Americans know that their ancestors were enslaved in the Americas, while others are not aware of their heritage. Some families may have arrived in the US from Africa or the Caribbean after slavery ended in the US, but for most Black American families, tracing genealogy and discovering heritage means working back through history into the records of US slavery.

How to Start

Researching African American genealogy requires a lot of preliminary work. Genealogists begin by researching family lines back from the present. The plan is:

- Start with known information, even if it’s your own birthdate and birthplace.

- Check with living relatives in case someone has preserved records, stories, or photographs.

- Work backwards from the present.

- Find records that link each generation back to each succeeding generation.

After checking for information held by family, a genealogist will attempt to locate records elsewhere to confirm that people are related to each other. Records may show birth dates, marriage dates, death dates, family members, and locations. Records may be held in collections created and preserved by the government. Many records may be on websites like FamilySearch or Ancestry. Others may be on other websites or may only exist on paper in a government or university archive. These records may include birth certificates, death certificates, census records, newspaper articles, and tax records. The more thorough a search, and the more documents found for a family, the better the chances to confirm relationships.

With each new document, the information needs to make sense. For example, a child is never born before its birth mother. Multiple people can have the same name, so a genealogist needs to check dates, places, and relationships to confirm that the record is for the right person.

Background Information

Researching African American genealogy, especially going back into slavery, requires knowing history. Here are some basic facts.

- The European African slave trade began in the 1400s.

- The first known enslaved Africans arrived in the continental U.S. in 1526.

- 1619 is considered the start of slavery in the US. That’s the year an English ship took more than twenty Angolan captives to Jamestown, Virginia.

- In 1662, Virginia wrote a law that gave the children of enslaved women the same legal status as their mothers. This began a new system that allowed for hereditary African American slavery. It created a large, politically powerless workforce recognizable by skin color.

- The laws of slavery treated enslaved Americans as property. By law, enslaved people could not form their own families and expect to keep them together.

- Slavery existed in every part of the US, from North to South, East to West. At times, up to half of the population of parts of New York City were Black and enslaved.

- In 1865, hereditary slavery ended with the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

- In the 1900s, millions of Black Americans moved out of the Southern US to try to find better and safer lives for themselves.

Scholars continue to write about slavery. Along with basic histories like Ira Berlin’s Many Thousands Gone, genealogists can find books and articles to explain every part of the system. Genealogists can do more accurate research if they understand the history and laws of slavery.

The Records of Slavery

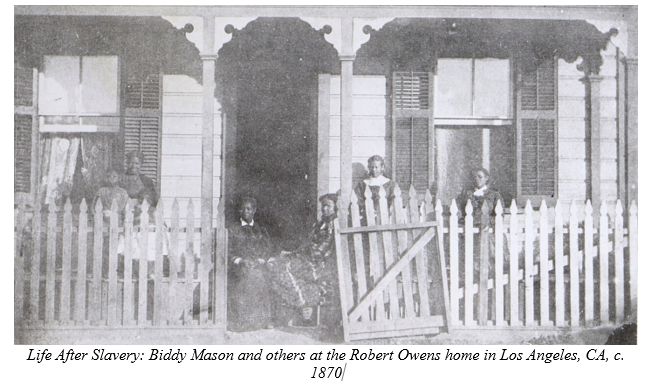

Many Black American families can trace their ancestors back to the 1870 census. That might be the first time a free person shows up by name on a government record. The following image shows famous Californian, Biddy Mason, in the 1870 census.

After Biddy Mason was freed, she became a wealthy Los Angeles philanthropist. Before a judge freed her in 1856, however, she was enslaved by Robert M. Smith and Rebecca Dorn Smith. Knowing the identity of her enslavers means that historians can trace many of her movements during her enslavement. Records about enslaved people were usually created by or for their enslavers, so tracing a family in slavery will require knowing the names of the enslavers.

Unlike Biddy Mason, many families don’t know the identity of the people who enslaved their ancestors. If the information exists—and it may not—you may find it in the following records:

- Records of the Freedmen’s Bureau. This short-lived agency was created to help people build a life after slavery. During the short time it existed, it created many records that may show the origin of freed people in slavery. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/freedmens-bureau

- WPA Slave Narratives. During the Depression, the federal government funded many historical projects. The Federal Writers’ Project had white teachers, librarians, and authors visit the elderly Black people in their communities to gather their histories. Some of these interviews can help families reconstruct their genealogy. https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writers-project-1936-to-1938/about-this-collection/

- Surveys of County Records. If descendants can identify the county where their enslaved ancestors lived, reading through the court records of the county may help connect enslaved people to their enslavers. https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/United_States_Genealogy

- Cohabitation Records. After slavery ended, many former slaves wanted to make their family relationships legal. Counties could register their marriages. These records are called cohabitation records. Some are available online, but some are only available in libraries or archives. https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Cohabitation_Records

- Slave Schedules. From 1790 through 1860, the federal census counted enslaved people. Except for a few exceptions, the census never included names, so slave schedules are of limited use. https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/United_States_Census_Slave_Schedules

These records are only a sample of what is available to discover a family’s heritage and history. There are often more records than descendants would suspect; however, if finding historical records does prove difficult, using DNA analysis to discover biological origins is proving very successful and opening many doors. Those interested in their heritage can often benefit from a combination of records-based and DNA research.

The processing of searching for one’s ancestry can be complicated but also enlightening and very rewarding, especially as one comes to appreciate the resilience and resolution required by early African Americans who were part of the brutal system of U.S. slavery. If you need help exploring your own family history, professional genealogists are available at Lineages to help!

By Amy

Sources

- Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/

- FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/

- “Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writer’s Project, 1936 to 1938,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writers-project-1936-to-1938/about-this-collection/

- “Facts About the U.S. Black Population,” Pew Research Center, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/fact-sheet/facts-about-the-us-black-population/

- “Family history, slavery and knowledge of Black history,” Pew Research Center, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/2022/04/14/black-americans-family-history-slavery-and-knowledge-of-black-history/

- “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” African American Heritage, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/freedmens-bureau

Images:

- Life After Slavery: Biddy Mason and others at the Robert Owens home in Los Angeles, California, c.1870. Picture in the public domain. Miriam Matthews Photograph Collection, UCLA Library Digital Collections, https://www.library.ucla.edu/collections/explore/miriam-matthews-photograph-collection/

- Enslaved families in the Gaines household, Hanover County, Virginia, c.1862, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC. No known restrictions on publication. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/96511694/

- The 1870 United States Census showing Biddy Mason living next door to her daughter Ellen Owens in downtown Los Angeles. 1870 United States Census, NARA microfilm M593. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration.