Becoming American: My Journey to Dual Citizenship

Born and raised in Northern Norway, I moved to the United States in 2001 to join my Idahoan husband. At the time, Norway didn’t permit dual citizenship, and giving up my Norwegian citizenship was out of the question. I love my native country and go there often. Having to present a U.S. passport to enter my birth country would feel like a betrayal. Additionally, my children couldn’t get Norwegian citizenship if I were to give up mine.

In 2020, Norway opened up to allowing anyone living in Norway who was a citizen of a different country to apply for Norwegian citizenship without giving up their native citizenship. However, if you were a Norwegian living abroad, you would lose your Norwegian citizenship if you applied to become a citizen of a different country. Finally, in 2022, the Norwegian government finally allowed Norwegians living abroad to keep their Norwegian citizenship in conjunction with foreign citizenship.

I received my first green card in the fall of 2001. This first card was temporary and granted due to my marriage to an Idaho boy. I guess the U.S. immigration services wanted to ensure I was in the U.S. for the right reasons before providing a permanent green card. After a couple of years, I was asked to return to immigrant services to prove that my civil status had not changed. I was asked to provide my husband, any children, and lots of documentation on joint address and bank accounts. The process was slow, but I finally had my permanent green card after a long wait period. Except it wasn’t permanent; it had a 10-year limit. Every 10 years, I would have to go through the process all over again.

Having already renewed my green card once at a pretty hefty fee (as a friend said, “Oh, you’re paying a membership fee to the U.S.”) and coming up for another renewal in 2025, I decided it was time to look into the citizenship process.

The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) has a great website, making the application process relatively simple. The needed form was N400-Application for Naturalization. After adding my A-number from my green card, I filled out all pertinent information regarding myself: a spouse of a U.S. citizen, full name and maiden name, birth information, the date I became a lawful permanent resident, height, weight, eye color, and so on.

The application asked in-depth questions about my marriage and my husband’s previous marriage. Since we were married in Sweden, I had to provide a certified translation of our wedding certificate. I also had to upload my husband’s divorce papers. This was all provided when I applied for my green card, but I guess the different departments don’t necessarily communicate with each other. The application also asked about employment and education during the last five years and any trips outside the U.S. for vacation. Fortunately, my passport had stamps that included dates when I entered other countries and the U.S.

The last section of the application form had 37 questions, of which several had three to seven sub-questions. These questions covered

- Previously lying about being a U.S. citizen

- Owing tax money

- Any involvement with communist or totalitarian parties

- Using weapons to harm or threaten someone or hiring someone to do it for me.

- Participating in torture, genocide, murder, or rape

- Participating in any military or police unit.

- Being involved in forcibly detaining people

- Any criminal involvement with weapons

- Committing any crimes or offenses

- Prostitution, smuggling, bigamy, illegal gambling, assisting in illegal entry into the U.S., failure to pay child support or alimony, and lying to U.S. government officials. (I do find it interesting that they chose to group these together…).

A few weeks after submitting my application, I received Form I-797, a notice of action, from the USCIS informing me that they had received my application, would schedule me for an appointment to provide my fingerprints, photograph, and/or signature, and that my green card had been extended by two years. With such a long extension, I expected the process to take a long time.

A few weeks later, I received a letter informing me that they were able to use my fingerprints, photograph, and signature on file. However, they would not reimburse me the fees charged for fingerprints, photos, or a signature – go figure. Not having to drive an hour and a half to the nearest USCIS Application Support Center was still a win. Then the expected long wait began…

I was surprised to learn only a couple of months later that I was scheduled for a meeting with a USCIS representative. During this meeting, “you will be tested on your knowledge of the government and history of the United States. You will also be tested on reading, writing, and speaking English.” Having lived in the U.S. for over twenty years, I was not concerned about the linguistics test at all. Nor was I concerned about U.S. geography or history. But, as I could not vote all those years I’d been in the country, I had not been involved with or paid particular attention to politics beyond what was generally found in the media.

The USCIS has an app with over 100 questions commonly asked during the civics test. You are expected to get at least six out of ten questions correct during the test. The questions were divided into four categories

- History

- Which war took place…?

- Who was the president during … war?

- When was the Declaration of Independence signed?

- Name three states that were part of the original 13 colonies. Etc.

- Geography

- Name three states that border Canada.

- Name a state that borders Mexico.

- Which ocean is to the left of the United States?

- Name a U.S. territory. Etc.

- Politics

- Who is the current president?

- Who is the current vice president?

- Who do the members of the House of Representatives represent?

- How many years does a senator serve? Etc.

- Laws and Regulations

- Who signs new laws?

- Name some changes that came with the Fifth Amendment.

- How old do you have to be to vote?

- What are some rights that come with becoming a citizen? Etc.

Because I have lived in the US for more than 20 years and I am over 50, I didn’t have to do the English tests. The civics test, however, was part of my interview. I believe the computer randomly pulled up questions for the USCIS representative to ask. Having worked hard on the questions in the app, I felt confident when the questions came. But, three of the six questions the representative asked were not among the questions in the app. The most surprising question, which only one of the many Americans I’ve talked to could answer correctly, was, “How long can a U.S. president serve?” I immediately answered, “8 years.” Nope! A vice president can serve two years as acting president and two full four-year terms as president, for a total of 10 years.

After the civics test and my interview, the USCIS representative informed me that he would recommend me for the Oath of Allegiance. This allowed me to ask some questions. Two years earlier, when Norway opened up for dual citizenship, I had looked into what the process of applying for American citizenship would entail. Everything looked dandy and fine until I got to the Oath of Allegiance, which reads as follows,

“I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen; that I will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform noncombatant service in the Armed Forces of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform work of national importance under civilian direction when required by the law; and that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; so help me God.”[1]

I love my native country, Norway, and I love and support the royal family (yes, Norway has a king and a queen). This oath was asking me to “absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have been a subject or citizen.” There was just no way I could renounce my king and queen. I did several searches online to see if maybe there was a different oath for those obtaining dual citizenship, but there is only one Oath of Allegiance. Though the oath used today was officially created in 1906, it built upon the oath that came with the first naturalization law in 1790.[2]

Since I had the opportunity to ask the USCIS representative about the Oath of Allegiance, I expressed to him that I felt I was being asked to lie under oath. As a dual citizen, I was not renouncing my king, queen, or native country. He understood my concern well and could see how the thought of renouncing my country affected me. He explained simply that I was not renouncing my country but that if Norway and the U.S. ever went to war against each other, I pledged to take the U.S. side of the war. I’m not sure this explanation is accurate, but it is one I could live with – I doubt that Norway and the U.S. will ever be on different sides of a war. And should that ever happen, I will decide then which side to take.

A few weeks later, I was scheduled for my oath ceremony. Since the room they used for the ceremony was quite small, I was allowed to bring only one person with me. After passing through security, they checked my invitation and ensured nothing important had changed in my life since the interview. I then had to render my green card as I would no longer be an alien.

When we entered the “oath room,” we all had assigned seats – I was number 12. The room could fit 50 applicants, but only 31 were scheduled that day. Our first task was to fill out a voter registration form to ensure our full participation in American democracy. We were also informed that any children under the age of 18 would receive American citizenship with their parents without having to go through the naturalization process.

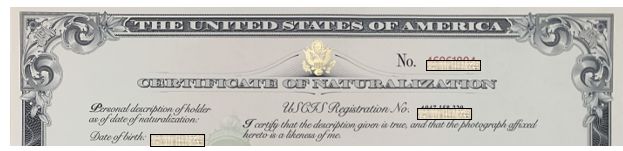

The official meeting started with all singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The 31 who participated in the ceremony represented 19 countries, and all were asked to rise as their country was read. Most countries only had one representative, though a couple of countries had two or three. The largest group came from Mexico, with nine applicants. Other countries included Canada, Germany, Spain, Russia, South Africa, Libya, Peru, Chile, Namibia, Syria, and more. A short speech was followed by all applicants raising their right arm to the square and reciting the Oath of Allegiance before we were all handed our Certificate of Naturalization.

So why did I decide to apply for citizenship after living as an alien in the U.S. for 23 years? The main reasons were:

- Norway had opened up for dual citizenship, and I no longer had to give up my native citizenship to become American.

- The “membership fee.” It would be cheaper in the long run to have citizenship than to keep renewing my green card.

- As an alien, I could risk not being let back in if I left for an extended time period, for example, to care for aging parents in Norway.

- I wanted to be able to vote and have a say in the society I live in.

Going through the naturalization process has made me think of all those who came to the U.S. over the last 200+ years for religious, social, or economic reasons. They all came with dreams and hopes. For some, these dreams and hopes were fulfilled. For others, they were crushed. There are people coming to the U.S. today with hopes and dreams. Several newly naturalized citizens spoke at the Oath of Allegiance about their journey to citizenship and how living in America has changed their lives. Since I obtained my citizenship for practical reasons more than anything, I didn’t expect the experience to be emotional. However, I must admit tears filled my eyes throughout this process, and I am proud to be an American!

If you need help learning about your ancestors’ immigration and naturalization, let Lineages help!

Torhild

[1] “Naturalization Oath of Allegiance to the United States of America;” website article, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (uscis.gov : accessed 12 March 2025).

[2] “History of the Oath of Allegiance;” website article, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (uscis.gov : accessed 12 March 2025).