Fathers : Then and Now

In every family tree, there are names that rise above the rest—not because they held power or fame, but because of the quiet strength they carried through ordinary life. For our family, one of those names is Ivin Victor Rasmussen, a storekeeper, musician, prospector, and devoted father who spent nearly 80 years in the small town of Fountain Green, Utah. Ivin’s story reflects a kind of fatherhood rooted in constancy, service, and love—offering a powerful window into what it meant to be a father in the early 20th century.

But Ivin’s life is also part of a longer chain. As we trace the fathers who came before him, and those who have followed after, we see a pattern emerge: fatherhood itself has evolved—quietly and dramatically. From survival and provision to presence and emotional connection, the role of fathers has shifted with each generation. By reflecting on Ivin’s life and the paternal legacies woven into our family line, we gain insight into how fatherhood was lived, felt, and redefined across time. This is not just a spotlight on one man—it’s an invitation to consider what it means to be a father, then and now, and the legacies we carry forward.

Ivin Victor Rasmussen

Every family tree has a figure who quietly anchors generations through work, devotion, and everyday heroism. For our family, that man was Ivin Victor Rasmussen, a devoted husband, father of seven, and lifelong storekeeper in Fountain Green, Utah. His life, while rooted in a small rural town, left a wide impact through steady service, deep generosity, and community involvement.

Roots in Fountain Green

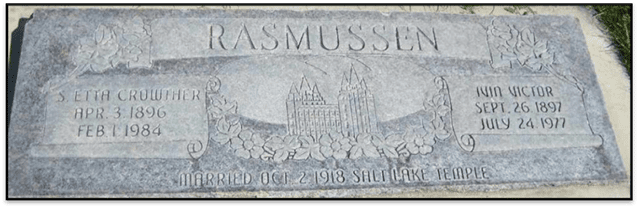

Ivin Victor Rasmussen was born on September 26, 1897, in the modest settlement of Fountain Green, located in central Utah’s Sanpete County. The town had been founded just a few decades earlier by Latter-day Saint pioneer settlers and remained a close-knit agricultural and religious community during Ivin’s lifetime.

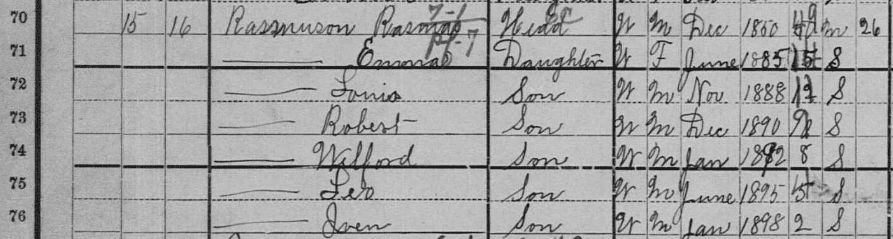

He was the youngest of eleven children born to Danish immigrants Rasmus Rasmussen and Ane Christensen. Five of his siblings were born in Denmark before the family immigrated to Utah in the 1880s. Three of his brothers died in early childhood, and Ivin grew up as the baby of a large, industrious family. Ane was the first to move to the United States taking her children with her. After a brief period of separation, Rasmus reunited with the family in Fountain Green, where they would build a life rooted in faith, resilience, and hard work. The following is the family found in the 1900 U.S. Census.

A Life of Hard Work and Integrity

From a young age, Ivin exemplified the value of honest work. At just 12 years old, he began working at the Fountain Green Co-op Store, delivering goods and hauling freight from the railroad depot by buggy. He stayed in the mercantile business his entire life, eventually founding his own store in 1918, which he would operate independently for nearly six decades.

His store was a community cornerstone. During the Great Depression, Ivin often provided food and goods to transients or struggling families without expecting payment. His shop was stocked with everything from fabric and canned goods to hardware and even parts for farm equipment. He frequently bartered with local farmers, trading goods for crops. His generosity and service-minded approach made him beloved by many.

Family Man and Community Builder

In 1918, Ivin married Sarah Etta Crowther. Together they raised seven children—Ruby, Victor, Gayle, Joyce, Doris, Carl, and Camille—in a small house he built himself “down the lane” from his childhood home. The house, though humble, was always full of warmth, work, and laughter. Despite space limitations, the Rasmussen household remained a stronghold of love and faith, with many of his descendants remaining in the community to this day.

Outside of family and work, Ivin was also deeply engaged in community life. He played the drums in the town band, helped run the local theater projector, hosted roller-skating nights in the old dance hall (which he later converted into his store), and took hundreds of photographs at family gatherings and town events. He was a fixture at Lamb Day, Fountain Green’s annual celebration.

Later in life, Ivin developed an interest in prospecting and would often disappear into the mountains west of Nephi, returning with rocks and stories to share with curious grandchildren. He also maintained fruit orchards and a large garden, which became a treasured source of shared meals and summer memories.

Legacy of Service and Character

Ivin’s greatest legacy may have been the example he set. He lived by a simple code: work hard, give freely, and love deeply. He never asked his children or grandchildren to do anything he wouldn’t do himself. Whether running the store, tending his orchard, or guiding his family, Ivin was unwaveringly present.

He and Etta celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 1968. By the time of his death in 1977, Ivin had become a grandfather to 27 and had dozens of great-grandchildren. His wife Etta lived until 1984, completing a life partnership that inspired generations.

Reflections on Paternal Legacy

What does fatherhood look like when lived with quiet consistency? Ivin wasn’t famous. He didn’t leave behind wealth or titles. But in Fountain Green, his name is remembered with admiration and affection. Every father leaves a mark; sometimes in names carried forward, sometimes in family stories, and often in values passed down like heirlooms. Whether your family tree stretches back through pioneer settlements, immigrant journeys, or industrial cities, one thing is certain: the experience of fatherhood has transformed dramatically over the past two centuries.

What it meant to be a father in the 1800s is not what it means today. And yet, across that sweeping change, some elements remain strikingly the same.

Provision to Presence

In earlier centuries, a father’s success was measured by what he could provide: food, shelter, and survival. On farms, in factories, or as tradesmen, fathers were often distant figures—early to rise, late to return, and rarely seen in caregiving roles. Their love was expressed through labor, not words.

Today, that paradigm has shifted. While providing is still part of fatherhood, there’s a growing emphasis on presence—being emotionally available, involved in daily routines, and attentive to children’s mental and social well-being. Modern fathers change diapers, show up for ballet recitals, learn about emotional regulation, and often split household responsibilities more equally.

Legacy to Intention

Earlier fathers often saw their legacy as a name, a plot of land, or a family business. Today, legacy is just as likely to mean instilling values: curiosity, compassion, creativity, faith, or resilience.

Modern fathers are asking more questions:

- What habits or emotional patterns am I passing down?

- How do I make space for my child to become who they’re meant to be?

- What do I wish I had received from my own father?

Different Eras, Shared Challenges

While expectations have changed, many of the pressures fathers face have remained—just in new forms:

- In the 1800s, fathers feared for their children’s survival. Today, fathers fear for their children’s mental health, safety online, or economic future.

- In the 1900s, fathers worked grueling hours away from home. Today, even remote-working dads may feel like they’re never fully “off duty.”

- In every era, fathers have wondered how they can do more for their family or for the community.

And yet, generations of fathers have shown up anyway: to build, to teach, to encourage, to adapt.

Explore Your Own Paternal Line

Do you have an ancestor like Ivin in your family tree? Someone who wasn’t famous, but formed the backbone of their community or family? Try searching census records, immigration logs, and draft cards to build your own paternal biography. Their stories are closer than you think.

Fatherhood is not a fixed definition—it’s an evolving relationship. What binds all generations of fathers together is the desire to do right by their children, even when the world keeps changing. Whether your paternal line includes farmers, immigrants, business owners, or artists, they each contributed a chapter to your story. And now, fathers today are writing their own.

If you want help exploring your own paternal ancestry, Lineages can help!

James

Image Sources

1 – Photo in the possession of the author.

2 – Rasmas Rassmuson household, 1900 U.S. Census, Fountain Green, Sanpete, Utah, page 1B, ED 123; imaged in “United States, Census, 1900,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MMR5-9TW?lang=en : 10 June 2025).

3 – Photo in possession of the author.