Freedman’s Bank Records

Following the end of the Civil War, the United States government established firm control over the South. The laws prevented former Confederates from holding office. From 1865 and 1877 this time period is known as the Reconstruction Era. At first, hopes were high for the newly freed slaves, known as Freedmen. There were new programs to assist them in their transition, and the records left behind, like in the Freedman’s Bank records, provide substantial genealogical information that can help us track the ancestors from enslaved workers to American citizens.

Freedman’s Bank Records

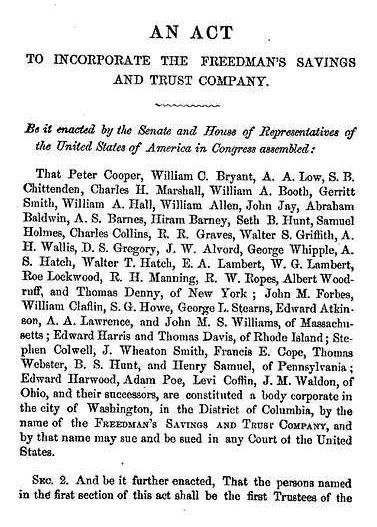

An important source of the Reconstruction Era is the Freedman’s Bank Records. These come from the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. It was chartered by the U.S. Government in March 1865 with the intention of being a place to save money earned by the freedmen.[1] It wasn’t a commercial bank, meaning that it didn’t give out loans, and the deposits were not backed by the federal government. It had many locations in the South and one in New York and another in Washington D.C.

This banking company only lasted nine years. The collapse of the company was brought about by mismanagement and fraud. The Panic of 1873 helped precipitate its final closure in 1874.[2] The Freedmen lost a lot of money. They were inexperienced with earning a wage and had a lot to lose. They become more distrustful of banks and the government.

The Freedman’s Bank Records are available on FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com. Both websites include search parameters for father, mother, spouse and children. Ancestry has an added parameter for the date of the deposit. Depositors were both male and female, and deposits were sometimes made on behalf of others, like a grandmother for a young child.

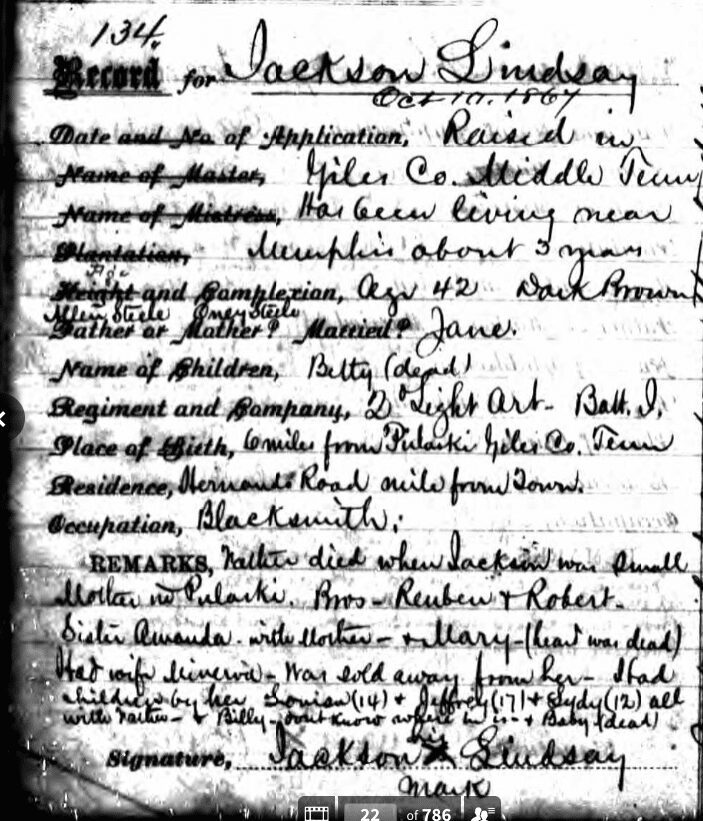

The possible information found in these bank records include many items: the depositor’s name, the date of the deposit, employer’s name, name of plantation, age, height, complexion, parents’ names, whether or not the depositor was married, birthplace, residence, occupation, names of children, names of brothers and sisters, and other remarks that were thought important.

It can be difficult to track these freedmen. Enslaved Africans didn’t have surnames until 1865, but many of them chose surnames of their previous owners or other people they knew. In addition, since enslaved family members were often forcibly separated, they likely bore different surnames. It is important to check relationships closely and not expect that close relatives had the same surname.

An example is the application of Jackson Lindsay, which shows at the top where he was raised and where he has been living. Written above “father or mother†are the names Allen Steele and Omey Steele. It appears that his parents had a different surname than their son. Even though the surnames don’t match, the family relationship is explicitly written.

The remarks for this application have information about when Jackson’s mother died as well as the fate of his sister Amanda. This collection fills in a lot of biographical details on the family.

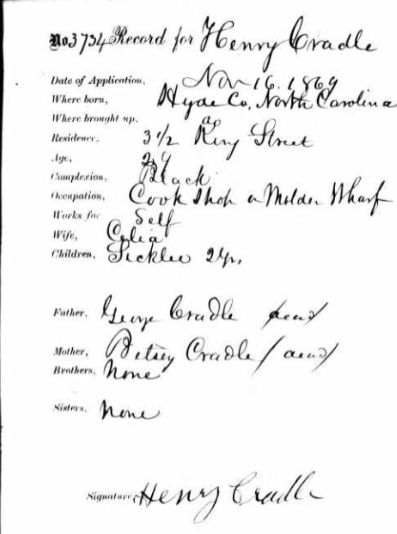

The applications were not standardized throughout the country or throughout the lifetime of the Freedman Savings and Trust Company. Most questions were the same. Information like age, birthplace, occupation and immediate family members are found on all bank records.

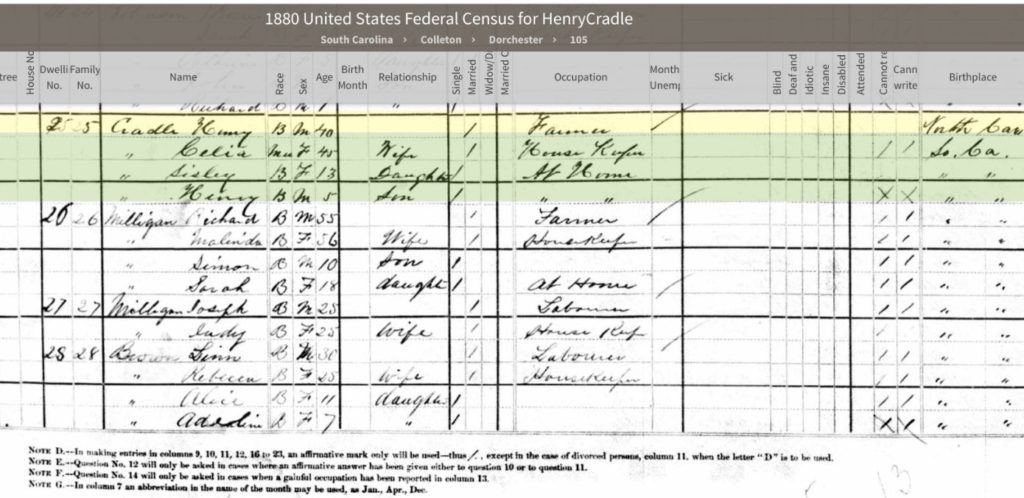

One can find an ancestor in these records by searching for the individual and his family relationships. For example, Henry Cradle had a wife named Celia and a child Sicklee, 2 years old. He was born about 1840 in North Carolina, with his residence in Charleston, South Carolina. There is an abundance of information that will help locate him in the U.S. censuses. If one searches for his name into the 1880 census, there is only one result, a Henry Cradle living in Dorchester, North Carolina.

It is usually best to move back through the censuses to the 1870 and 1880 enumerations, then look for your ancestors in the bank records. The Freedman’s Bank Records are an important tool for African Americans following emancipation, and for connecting the family members who otherwise would have been lost to us today. The collection doesn’t include everyone, but it has a lot of unique information that should recreate families separated by slavery.

by Kristlynn

- Weinstein, Lynn and posted by Ellen Terrell, “America’s Compounding Debt: The Freedman’s Bank,†Library of Congress, online 18 July 2019. https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2019/07/americas-compounding-debt-the-freedmans-bank/

[1]https://www.britannica.com/topic/Freedmens-Bank

[2]https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2019/07/americas-compounding-debt-the-freedmans-bank/

Have you done any online research with Freedman’s bank records? Let us know in a comment below!