German influences in the United States – Part One

Many Americans have German roots somewhere in their family tree. Until recently, German Americans largely stuck to their own communities in the New World. Their practices affected how their records were created, which we must remember as we research them. This blog will focus on these practices, and the next blog will focus on applications in research.

Records created

The German Society of Maryland was formed to combat abuse that was being dealt to newly arriving German immigrants. Such abuse included using agreements written in English to force new immigrants into indentured servitude with terms they didn’t understand. The German Society of Maryland monitored incoming ships containing German immigrants and built churches, schools, and orphanages. Their surviving records were donated to the Maryland State Archives.

In the colonial era, British settlers were not immigrants. Therefore, immigration records created during that time pertained to settlers from Germany, Switzerland, and other European countries. Beginning in 1727, the Pennsylvania colony kept records of Oaths of Allegiance and Oaths of Abjuration of foreigners—mainly Germans. These records are published as Pennsylvania German Pioneers and are the closest colonial records to German passenger lists.

During the colonial era, Germans were the only large group needing naturalization. Until 1740, this was done by an act of the Colonial Legislature, which Parliament ratified. After 1740, this was done by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The legal waiting period was seven years, typically around fourteen years after the immigrant’s arrival. These naturalization records often indicate when the immigrant last took the sacrament, so it can help determine who your ancestor went to church with.

Germans went to church together, attending German churches with German clergy; therefore, church records are invaluable for researching German American ancestors. Baptism records almost always name the child, parents, and sponsors and give birth and baptism dates. Sometimes, they indicate the relationship between the child and the sponsors. Anabaptists practiced adult baptisms, so they don’t usually have good birth records.

Marriage records almost always name the bride and groom and give the marriage date. Sometimes, they name the fathers of the bride and groom and give the places of residence. Occasionally, they’ll give the birthplaces of the bride and groom. If either the bride or groom was remarrying, the record might mention the former spouse.

Burial records almost always name the deceased and give the date of burial. Sometimes, they’ll give the date of death or place of burial. Occasionally, they’ll provide family info such as the spouse’s name or number of children or give the birthplace of the deceased.

Confirmation records were not as well preserved as other church records, but they can contain valuable information where they are found. They almost always give the name of the confirmed. Sometimes, they’ll provide the confirmed age or the father’s name. Occasionally, they’ll list the skills of the confirmed.

Communicant lists almost always name those communing and are organized by family. Sometimes, they cross out the names of people who left the congregation.

Another practice Germans kept was baptismal certificates with folk art, which contained genealogically valuable information. This is called Taufscheine or Fraktur.

With church records, it is important to note that there was a shortage of clergy in the German churches. Some parents would have their children baptized by the next clergyman who came into town just to have them recorded. It was also a common practice for multiple churches to share a church building. These practices affect where church records are kept and where they can be found.

The German communities in America also kept their own newspapers printed in the German language. Newspapers can be helpful for researching your ancestors on both sides of the ocean. Newspapers kept in Germany included those dedicated to local or regional news, state or district-level governmental newspapers, emigration newspapers, military regiments, newspapers related to various occupations, and police newspapers.

German newspapers often contained information about emigrants, both legal and illegal. The police newspapers were how the German police kept track of who was coming in and out of town. Legal immigrants may have posted a notice of their intention to emigrate. Illegal emigrants may have appeared in the summons in the newspapers after leaving, either because the authorities suspected them of illegally emigrating or because they failed to report for military service.

Besides newspapers, there are other emigration records of your ancestors leaving Germany. Cities kept records of people coming into and out of town, and some have been sent to the state archives in Germany. To legally emigrate, an ancestor had to get permission or a release of citizenship. This record usually contains the emigrant’s name, birth date, birthplace, current residence, occupation, names of spouse and children, sometimes destination, port of departure, and names of parents and siblings. Not all of these records are extant, especially from early times. Note that only those who emigrated legally are covered in these records.

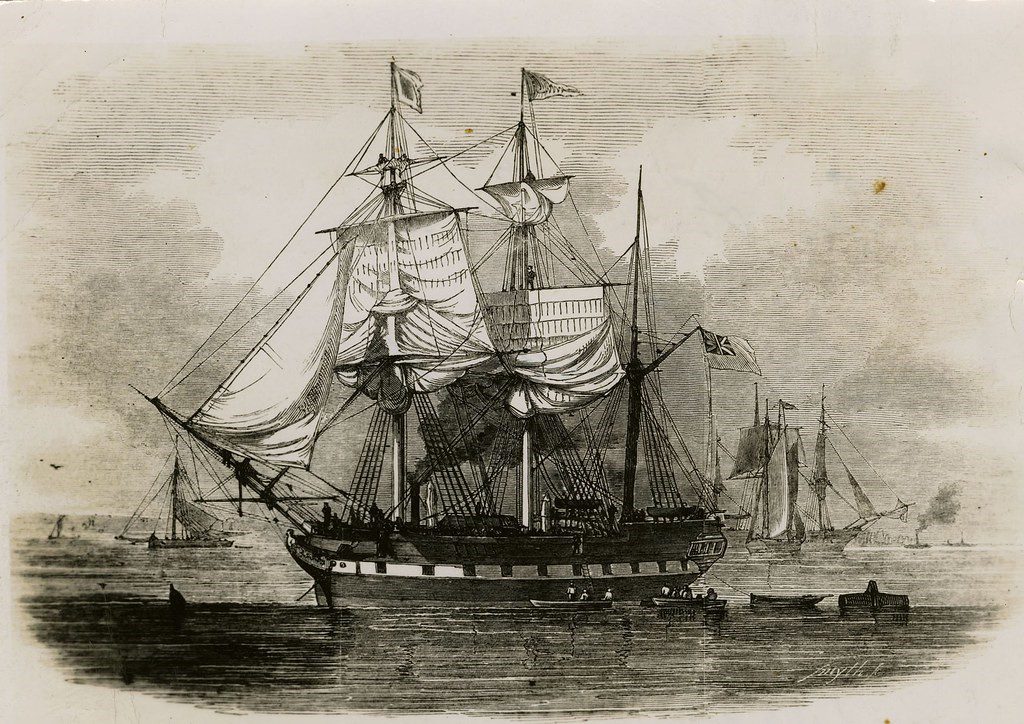

Many German emigrants practiced step migration, moving to a port city like Bremen or Hamburg before leaving for America. In the port city, the emigrant would establish residency and work to earn enough money to buy passage. Sometimes, the emigrant would apply for citizenship to get a better job. Records found of the emigrant in the port town include passenger lists, residency papers, and citizenship applications.

Hamburg and Bremen became major ports out of Germany in the nineteenth century. Hamburg was a major port from the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth century. 80% of the immigrants leaving there were headed to the U.S., and about one-third were German. The remaining two-thirds were from other Eastern European countries.

Bremen was slow in becoming a major port until 1830. Then, it became the most important continental port in the decades before WWI. Ships bringing tobacco from Baltimore to Bremen took passengers on the return journey. Many emigrants stayed in hotels and boarding houses before departure.

Sometimes, passenger lists have a line crossing out a name. This means the person bought the ticket and didn’t show up, or they were listed twice. On arriving passenger lists, LI means the passenger was detained. Sometimes, the certificate number of arrival was added to the passenger list.

Now that we’ve looked at some record practices kept by our ancestors and the scribes in their day, the next thing we need to know is how that affects research. The next blog will cover this.

By Katie

Resources

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/german-research-for-the-everyday-american

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/the-voyages-of-our-german-immigrants/?search=german

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/get-with-the-times-german-newspaper-research/?search=german

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/the-palatine-immigrants-tracing-and-locating-18th-century-german-immigrants-online/?search=german

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/searching-for-a-pennsylvania-german-ancestor/?sortby=newest&search=german

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/is-this-the-end-taking-your-german-brick-walls-down-piece-by-piece/?sortby=newest&search=german

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/german-names-and-naming-patterns/

- Buiter, A. S. (2020). Tracing Immigrants through the Port of New York: Early National Period to 1924. New York Genealogical and Biographical Society.

- Freilich, K. H. (2016). NGS Research in the States Series: Pennsylvania (B. V. Little, Ed.; 3rd ed.). National Genealogical Society.

- DeGrazia, L. M. (2013). NGS Research in the States Series: Research in New York City, Long Island, and Westchester County (B. V. Little, Ed.). National Genealogical Society.

- Shawker, P. O. (2008). NGS Research in the States Series: Maryland (K. Freilich & A. C. Fleming, Eds.). National Genealogical Society.

- Clint, F. (1976). Pennsylvania Area Key (2nd ed.). The Everton Publishers, Inc.

- All photos are public domain