Happy DNA Day!

First celebrated in 2003 by proclamation of both the Senate and the House of Representatives, DNA Day is an unofficial U.S. holiday celebrated every year on April 25. While the original proclamation didn’t establish it as an annual event, researchers, educators, and genealogy enthusiasts have continued the tradition of celebrating DNA every year.

April 25 was chosen to commemorate the 1953 article in Nature by James Watson, Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin, and others, describing the structure of DNA—an achievement that revolutionized science and medicine, and today, powers a new era of genealogical research.

Why Use DNA in Family History Research?

For those who haven’t dipped their toe into the world of DNA: Can you research your family tree without using DNA? Absolutely! But might you be missing out? I’d say so! In this article, I’ll walk you through what DNA testing can do for your research, what to expect from your results, how to get started, and share some solved cases to illustrate just how transformative this tool can be.

More Than Just ‘How Irish Am I?’

Many people take DNA tests simply to discover their ethnic makeup. It can be satisfying (and fun!) to learn how Irish, Italian, or Scandinavian you are. These results can offer a general sense of your ancestral origins, but they’re not very precise—and the science is still evolving.

Some test-takers aren’t necessarily interested in deep genealogical research (or responding to messages from people like me), but I’m still glad they’ve tested. Why? Because their DNA helps solve family mysteries for others. Even without providing family trees or responding to my messages, their presence in a match list can provide crucial evidence.

Connecting with Living Family

Your DNA match list is a great way to connect with both close and distant relatives. Some of these matches may be actively researching their family tree, while others might hold memories, heirlooms, or records you’ve never seen.

Reaching out to matches can lead to the discovery of old family photos, letters, or simply a connection with someone who shares part of your story. And even if a cousin match doesn’t respond, their shared DNA can still help you piece together the larger puzzle.

Confirming or Challenging Your Family Tree

It’s a beautiful and satisfying experience to compare years of traditional research with DNA analysis and find that everything aligns. But it’s also helpful—and necessary—to expect the unexpected. When my mother tested with AncestryDNA, we quickly discovered that the man she believed was her grandfather was not biologically related to her. Fortunately, I didn’t know that side of the family personally, which made the news easier to process. Still, I mourned the loss of a beloved family line I had spent years researching.

In time, I realized this new information didn’t erase my family, it simply added to it. There was another line to explore, and I didn’t have to “give up” the original great-grandfather’s story entirely. That revelation in 2018 was my springboard into learning how to analyze DNA results. Soon, I was solving mysteries in my own match list, volunteering as a search angel, and eventually taking on client work, including complex cases to identify unknown 2nd or 3rd great-grandparents.

Make New Discoveries with Autosomal DNA

Autosomal DNA testing examines the 22 pairs of chromosomes you inherit from both parents, providing a broad view of your genetic heritage. Because you inherit 50% of your DNA from each parent, autosomal tests are great for uncovering relationships across both sides of your family tree.

However, autosomal inheritance is random. You may inherit around 25% from each grandparent, but in reality, the distribution varies. One person might inherit 30% from a grandparent, while a sibling receives just 18%. This explains why siblings often have different matches or share different amounts of DNA with cousins.

Several companies offer autosomal DNA testing, and I usually recommend starting with AncestryDNA. They have the largest pool of testers, which increases your chances of finding useful matches. That said, other companies—FamilyTreeDNA, MyHeritage, and 23andMe—offer features that Ancestry does not. Fortunately, Ancestry allows you to download your raw DNA and upload it to some of these other platforms for free. You might also consider uploading your raw data to GEDmatch, a free site that enables more advanced comparisons across testing platforms.

Whenever possible, test your oldest living relatives—parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents. Their DNA can offer matches one or two generations closer to your shared ancestors. As your research progresses, consider testing specific cousins or relatives who might have inherited DNA relevant to solving your family mystery.

Y-DNA and Mitochondrial DNA: Targeting Specific Lines

Autosomal DNA is the best place to get started with DNA testing and is generally effective for solving mysteries within the last 5-7 generations. However, it has its limits—especially when a family line is underrepresented due to small families, few testers, or recent immigration. This is where Y-DNA and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) come in.

Y-DNA

Y-DNA is passed from father to son, making it ideal for tracing direct paternal lines. If you’re a genetic male, you can take a Y-DNA test to identify your paternal haplogroup and find others who share your same Y chromosome. If you’re not a genetic male or don’t descend from the line in question, you’ll need to identify a male relative who does—such as a brother, uncle, or cousin—to test.

Because the Y chromosome mutates slowly over time, your matches may share a common ancestor from hundreds of years ago. Some matches may share your surname, while others may not, depending on a number of factors. I recommend starting with the basic Y-DNA test at FamilyTreeDNA and upgrading as your research deepens.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

While Y-DNA traces the paternal line, mtDNA traces the direct maternal line—mother to child. All individuals inherit mtDNA from their mother, but only females pass it on. So, both men and women can take this test. This test can help identify maternal line relatives, but like Y-DNA, it’s most effective for deeper research and to confirm maternal line hypotheses with targeted testing of two individuals. Say you suspect that your ancestor and another woman were sisters. You could test matrilineal descendants of both lines to determine if that’s a possibility. It’s one more piece of evidence to help you understand your family history better!

Real-World Applications

(Last names have been omitted to protect the living)

One straightforward use of DNA is to identify a possible ancestor through DNA analysis, then locate traditional records to support the DNA findings. Take the case of Richard. His great-grandmother, Elizabeth, was born in 1856 in Wisconsin. Richard had her marriage record and death records for her children, so he knew her maiden name, but had not been able to identify Elizabeth’s parents.

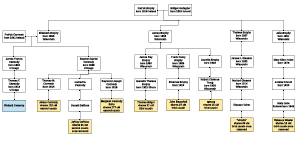

By analyzing Richard’s DNA results, we found multiple matches who were descendants of a couple named Patrick and Bridget. These individuals shared the right amount of DNA to be related in a way that made it possible that Elizabeth could be Patrick and Bridget’s daughter. Sure enough, the 1860 and 1870 U.S. census records in Wisconsin showed a daughter named Elizabeth, born about 1856, in Patrick and Bridget’s household. We also located an 1879 marriage record for Elizabeth’s sister which listed “Lizzie” with her maiden name as a witness. Without DNA, migration had made the research murky, but DNA pointed the way, helping break through a long-standing brick wall.

In another case, we used both Y-DNA and autosomal results to solve a puzzle. A client took a Y-DNA test and was confused when none of his matches shared his surname. After analyzing his autosomal DNA results, we discovered that his biological grandfather was not the man his grandmother was married to. By grouping his autosomal matches and identifying a cluster of relatives with no known connection to his documented family, we were able to determine the identity of his biological grandfather, giving him an entirely new branch of family history to explore.

One final example involves a man named David who never knew the identity of his biological father. Autosomal DNA testing revealed that David was half Ashkenazi Jewish—on his father’s side. Using this as a starting point, and comparing matches across multiple testing companies, we were able to identify his Jewish father. As it turns out, David’s English mother and his biological father had traveled to the United States on the same ship. Though no written record will ever confirm their relationship, the timing of their voyage, combined with strong DNA evidence, makes the case compelling.

DNA + Records = Your Strongest Genealogy Strategy

DNA has changed the landscape of genealogy research. It’s a powerful tool that can confirm years of traditional research, solve long-standing mysteries, and connect you with family you never knew you had. DNA is a partner to traditional research, not a replacement. If you haven’t taken a test, please consider doing so. If you’ve tested and haven’t looked at your results recently, revisit your matches. Consider reaching out to Lineages to find out if DNA can help solve a mystery in your family.

Happy DNA Day!

Laura

References:

- Watson, James Dewey; Crick, Francis Harry Compton (1953-04-25). “Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid” (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 737–738.

- Franklin, Rosalind Elsie; Gosling, Raymond (1953-04-25). “Molecular configuration in sodium thymonucleate” (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 740–741.

- Wilkins, Maurice Hugh Frederick; Stokes, Alexander Rawson; Wilson, Herbert R. (1953-04-25). “Molecular structure of deoxypentose nucleic acids” (PDF) Nature. 171 (4356): 738–740.

- “A concurrent resolution designating April 2003 as “Human Genome Month” and April 25 as “DNA Day”” (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. 27 February 2003, retrieved 22 April 2025.

- “Autosomal DNA” from ISOGG Wiki, https://isogg.org/wiki/Portal:Autosomal_DNA, retrieved 22 April 2025.

- “Y-chromosome DNA” from ISOGG Wiki, https://isogg.org/wiki/Portal:Y-chromosome_DNA, retrieved 22 April 2025.

- “Mitochondrial DNA” from ISOGG Wiki, https://isogg.org/wiki/Portal:Mitochondrial_DNA, retrieved 22 April 2025.

Photo credits:

DNA structure: PublicDomainPictures at pixabay

DNA matches tree: created by the author

Family: Rajiv Perera on Unsplash