Homesteading in the United States Part 1

The homestead act, passed in 1862 and enacted in 1863, lasted 123 years. Two hundred seventy million acres of land—10% of land in the U.S— was homesteaded. Homesteading provided opportunities for women, African Americans, immigrants, and other minorities to own land in the U.S. communities based on ethnic or religious groups formed around homesteading land. Today, one in three Americans are descended from homesteaders. If your ancestors were homesteaders, this blog series is for you.

Homestead acts and implementation

The homestead act drew settlers to the West, where lay much unclaimed land and allowed farmers to claim free land. 160-acre tracts were given to settlers on the condition that they lived on the land for five years and improved it by building a home and growing crops. After living on the land for at least six months, settlers had the option to buy the land for $1.25 per acre.

After five to seven years, the homesteader could prove their claim, which involved testifying about their improvements on the land and the value thereof. This process also required witnesses, who were usually neighbors, to testify. Once the claim was proved, a patent would be issued, indicating that the settler now owned the land. Five years was the minimum time before a settler was allowed to prove their claim, and seven years was the maximum time before the claim was canceled. Union veterans could apply their military service toward their residency requirement.

Who exactly was eligible to homestead? The law did not specify white males, so formerly enslaved persons and women were among the homesteaders. African Americans who homesteaded could own land and thereby gain true freedom.

A homesteader had to be a U.S. citizen. An immigrant did not have to be a citizen to start the process but had to have naturalized by the time they finished it. Another requirement was to have never taken up arms against the U.S., so Confederate veterans did not qualify. This was meant to prevent the spread of slavery to the West. However, Confederate veterans were later allowed to claim homesteads in their former Confederate states.

A homesteader had to be the head of household and old enough to vote; this was usually the husband. However, a woman who was the head of household also qualified. This included single women, widows, abandoned wives, and wives of men incapable of running a home. If the husband died or ran away after beginning the homestead process, his wife might have taken it over. Females who completed a homestead owned land in their own names.

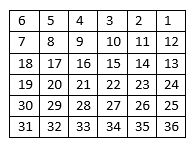

Homestead land was surveyed via the Public Land Survey System, which counted off townships and ranges from a central meridian point. Each township-range area was a 36-mile square, divided into 36 sections, and numbered according to the chart below. Each section is divided into quarters, with each quarter being 160 acres.

Assuming the chart above is just Southwest of the base meridian, the legal description of the upper right corner would be the Northeast Quarter of Section One Township One South Range One West (abbreviated NE ¼ Sec 1 Tp 1S R 1W). The legal description of the bottom left corner would be the Southwest Quarter of Section 31 Township One South Range One West (abbreviated SW ¼ Sec 31 Tp 1S R 1W).

The first homestead was in Nebraska Territory. The homesteader who claimed it signed up on New Year’s Day in 1863, the first day the act came into place. The homestead national park now rests on that property. Montana had the most homesteads and the last homestead was in Alaska. The homestead act was repealed in most states in 1976, but Alaska continued until 1986. The last homestead was completed in 1988.

The following 30 states offered homestead land:

Aside from attracting farmers, homesteading also lead to the building of cities in the West as places to process crops. Urbanization and overpopulation in the east were push factors for migration, while land in the west was a pull factor. For immigrants, push factors included religious persecution, economic hardship, and political oppression. Pull factors included better living conditions, economic opportunities, and abundant and affordable land offered through the homesteading act.

Homesteading attracted many immigrants to the U.S., increasing the immigration rates. It attracted immigrants from Canada, Czechoslovakia, Egypt, England, France, Germany, Italy, Palestine, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and Yugoslavia. Owning so much land was unheard of in these countries. It was cheaper to buy land in America than it was to rent land in England. This appealed to European farmers who did not own land and to younger children where primogeniture inheritance was practiced (only the oldest son inherits the land). The 1870 census shows a higher percentage of foreign-born persons in the West than on the east coast. Additionally, the western states and territories saw massive population increases. Many homesteaders were first-generation immigrants.

With the advent of the transcontinental railroad, it was easier to migrate westward. The same year the homestead act was passed, congress also chartered the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroad companies, which connected their railways in 1869. Female homesteaders were more common after the railroad connected the East and the West.

The homesteading act changed several times throughout the years. In 1866, confederate veterans could homestead in their former Confederate states. The Sothern Homestead Act of that same year encouraged African Americans to obtain homesteads. A timber culture act in 1873 required the claimant to plant trees and had no residency requirement. Land allotments were increased to 640 acres in western Nebraska in 1904. In 1909 the homestead size was doubled to 320 acres. In 1913 the residency requirement was dropped to three years, which increased the number of successful homesteads. In 1916 the National Stock-Raising Homestead Act was passed, which granted 640 acres for ranching purposes. The northern territories saw increases in homesteaders once absences during winter were allowed.

Our ancestors’ experiences with homesteading

Ancestors who wanted to homestead would go to the nearest land office to apply for a claim. The application process involved filling out paperwork and paying a fee. They would then be given a 160-acre allotment of land, which they were to settle on and grow crops on. Paying a smaller fee got them a half tract (80 acres).

After the required residency time, they could prove their claim. This process created more paperwork than applying. The claimant and witnesses had to give testimony of the claimant’s residence on and use of the land. Witnesses were usually neighbors. Your ancestor may have witnessed their neighbors’ homesteads, whether or not they completed one themselves. If multiple neighbors were homesteading, they may have witnessed each other’s homesteads.

Proofs were only filed for completed homesteads. If the homestead was abandoned or canceled, there was no proof or testimony from witnesses.

The county clerk asked questions of the claimant and two witnesses, such as how long the claimant and his family had resided on the land, whether they had been absent, what kind of house had been built, what the land was used for, and whether the claimant intended to stay or leave. The witnesses were asked how long they knew the claimant, how far they lived from him, and who lived closer to him. After reading the questions and writing down the answers, the clerk was supposed to have the claimant and witnesses read over the answers—at least, the clerk would sign a statement indicating that he did so.

Witnesses were supposed to be disinterested parties, meaning they weren’t related and had no business connection. But this must not have been well enforced because many homesteaders had relatives as their witnesses.

Such a system should have been able to prevent fraud, but fraud still happened. The laws were not well written, so people and corporations intending to abuse the system could find loopholes. One example is someone who built a miniature house because the law did not specify feet—they measured in inches instead.

If a widow took over her deceased husband’s homestead, the homesteading papers would include his death date. In other cases, a single woman who married during the homesteading process, or a widow who remarried, continued the homesteading process with her new husband, and the homestead papers would include the marriage date. While a single man or single woman who began a homestead could continue after marrying, a husband and wife could not have separate homesteads.

To complete their homesteads, most women forged cooperative relationships with family, other women, and neighbors. They would use local help to build homes, plow land, plant, and harvest. To pay for this help, they would share the profits from their land. Male homesteaders would hire female neighbors to help with laundry, cleaning, cooking, and selling homegrown items. Many women worked as schoolteachers to support their homesteads.

If the homesteader was an immigrant, they had an additional step in this process. Before applying for homestead land, they had to have had their first papers filed for naturalization or have declared their intention. The immigrant had to have completed the naturalization process before proving their claim. If your homesteading ancestor was an immigrant, their naturalization papers may be included in their homestead files.

Conditions were harsh in much of the West, with the Rocky Mountains and deserts, harsh winters and summers, droughts, tornadoes, wildfires, and pests that destroyed crops. Experienced farmers knew what they were doing, but not every homesteader was a skilled farmer. Novice farmers had a hard time growing their crops. Only about 40% of those who began the homesteading process actually completed it. Some people abandoned their claims, going back east, and those claims were taken over by people hanging around the land offices. Many African American homesteaders could not afford to return east, so they toughed it out.

Once the homesteader owned the land, some stayed for generations, and others sold the land and moved on.

The next part of this series will cover where to search for homestead records and show homestead research in action.

Resources

- All images are public domain

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/the-homestead-act-of-1862/?category=records&subcategory=homestead1862

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/homestead-act-of-1862-following-the-witnesses/?category=records&subcategory=homestead1862

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/women-homesteaders-and-genealogy-bonus-webinar-for-subscribers/?category=records&subcategory=homestead1862

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/ladies-and-land

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/immigration-and-the-homestead-act-finding-your-ancestors

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/go-west-american-migration-1783-to-1900

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/ethnic-and-religious-community-formation-under-the-homestead-act

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/the-roots-beneath-your-feet-stories-from-homesteading-descendants

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/3-the-lay-of-the-land-using-american-land-records-in-your-family-history-research