My Genealogy Journey in Post-Soviet Russia

Before the Russian Revolution of 1917, genealogy was mostly a concern of the nobility as a means of confirming their belonging to the higher society and thus enjoy the privileges of status and position. If they were able to confirm their noble descent, they were listed in special Russian Nobility Genealogy books.

Little did it matter to most of the population, though, who were peasants. Their vital events were recorded in the church books of the Orthodox church, the main religion in the Russian Empire, as well as in chapels of other Christian denominations and Jewish synagogues. Additionally, since the 18th century, tsar Peter the First established Revision Lists, which enabled the government to coordinate taxes and recruit of peasants, bourgeois, merchants, and Cossacks, and left us precious documents with clusters of families already united according to their relationships.

Everything changed with the rise of the Soviets. The social estates were abolished for the loftier goal of forming a new, Soviet person. People ceased to talk about their past. It was not only uncomfortable, but even dangerous. Society faced persecution in order to build equality, and in so doing, lost part of their heritage.

A client saw this happen first hand: part of his family immigrated to Canada and the United States before the Russian revolution, and part of the family stayed behind in Belarus. A hundred years later, the immigrant’s descendants possessed a rich history of their ancestors including fantastic details, such as crossing the river in boots or hiding in a hay wagon, whereas the family that stayed in Soviet Belarus knew almost nothing about their ancestors, including the immigration of siblings.

People in Soviet times knew enough to reveal as little as possible. The religion was not welcomed anymore. The government took documents from churches and established ZAGS (civil registration offices) to record the births, marriages, and deaths of its citizens. NKVD (Soviet secret police) persecuted and executed millions of people.

In my experience, each genealogy case would have some victims of political repressions in the USSR. Each! In my own family there is a story of family members bringing parcels for 20 years to their father in prison, only to find out that he was executed 20 years prior, in 1937 – the same year he was taken. It is worth mentioning that an overwhelming majority of these people were as innocent of any anti-Soviet rebellion as you and me, and were taken only because there was a “plan” to take a certain number of people by a particular deadline. Together with World War II, political repressions add up to an enormous database that is continually updated.

My genealogy journey starts with my great-grandfather and WWII. I was taught about the importance of doing genealogy at church, but I really intrigued once I found out that Research Movement had found the remains of my great-grandfather who died shortly after arriving to the front line in WWII. Research Movement is an organization in Russia that is diligently fighting against the bureaucracy to receive a special permission from Federal Security Service to work on a particular piece of land in Central Russia.

They dig the upper layer of ground, about 10-15 cm, and find the remnants of the deceased WWII soldiers. They look for a medallion with a tiny scrolled paper where information about the soldier would hopefully be found. Then, they bury the remnants in a bed of honor, inform the relatives, and put the soldier’s data into the website. Thus, I received the medallion of my great-grandfather. Soon after, I found myself among the group of Research Movement taking an expedition to the Veliky Novgorod region. I not only took part in soldiers’ excavations as a small tribute to the organization that had found my great-grandfather, but also visited the mass grave where he was buried. Then I used the “Swiss roll” method, as I call it. I visited all the relatives I could find with a Swiss roll to accompany and collected precious memories about our family that they could share.

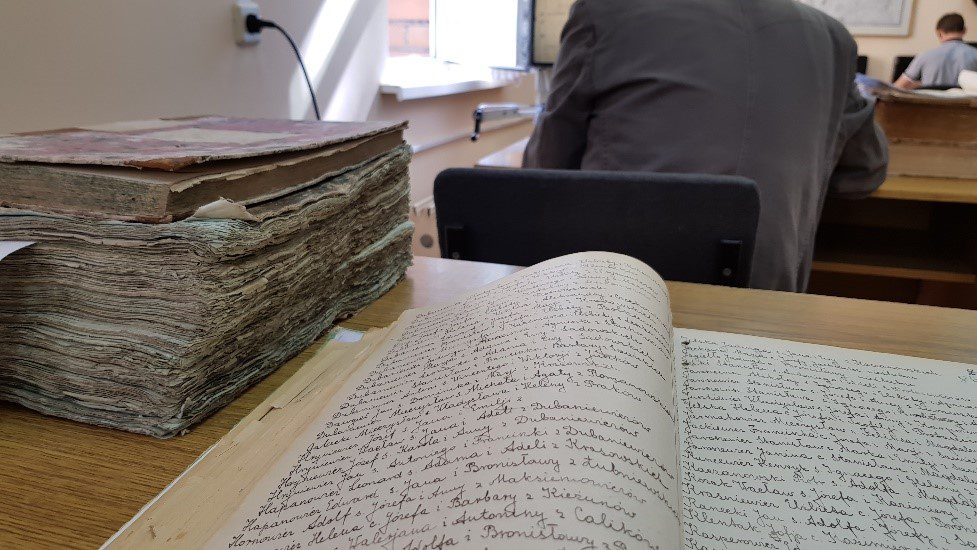

My next step was archival research. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many documents could be accessed in the reading-rooms of the archives and general interest in genealogy started to grow. I was among those few that started to do genealogy research, rather than the more common scientific and social archival research. Thumbling through the old pages fascinated me. The excitement of the discoveries was thrilling. Soon I realized that I loved genealogy research so much and had gained enough experience to help others!

I printed out leaflets and set out to find my first clients, while my mother urged me to go and find some “real” job. It turned out that people were receptive. After the long period of silence, people were willing to search, to uncover, to know. There were no universities in Russia that taught genealogy, so I received my Master’s degree in Russian History. When I wrote my senior thesis about genealogy research, my supervisors were skeptical because they did not consider genealogy an important scientific field. Nevertheless, I continued to investigate my clients’ cases and was getting more and more expertise with each one.

I travelled all around Russia and other post-Soviet countries – Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova, visiting village administrations, cemeteries, and museums, working in district, regional, and national archives. Each archive had a different set of rules. To access Saratov archive, for example, I had to stand in a queue for three hours before the opening of the reading-room in order to have the opportunity to work with the documents. Some archive workers were helpful and willing to assist, others said that I would never find anything and advised me to leave, even though I might have travelled more than 4000 km to access the records.

I have worked with a detective in Moldova, visited cemeteries in Ukraine, and organized family reunions in Belarus. I have traveled by plane, train, bus, and car to access different archives and locations, big and small, throughout Russia. I have met with Catholic priests, digitized records, and interviewed living relatives. I have witnessed how strangers can become close friends when we talk about family, how tiny clues are united to reveal the bigger picture, how an occasional person met during a family history expedition turns out to be the one who actually possesses the information that you need. Miracles accompany this work.

Not long after, I had an exciting opportunity to share my knowledge through lectures and seminars in the regional libraries of the major cities of Siberia – Krasnoyarsk, Novosibirsk, Tomsk, Omsk, Barnaul, Irkutsk, Ulan-Ude, etc. Several people gathered to learn how to trace their roots. Media wanted to know what genealogy is all about and kept asking the same question: “What for? Why do we need to search for our roots?” Well, it’s not about benefits of the upper class anymore, and the time has passed when silence was the only option. Now, I guess, it is all about connection. The desire to know about our ancestors is natural and strong. We want to know them. They deserve to be found, remembered, and honored.

With Lineages we have tackled immigrant cases, adoption cases, Jewish genealogy, and much more. I would have never imagined that in 2022 I would become an immigrant myself, taking my family and fleeing modern Russia for Brazil in fear of repressions and unwilling to support an unjust war. Luckily, my genealogy research has not been thwarted, with the increased accessibility of digitized records and local connections replacing the need to work in-person in the archives. So the journey continues: with each new discovery in my personal ancestry, with each new client’s case. I love this journey. I hope you enjoy yours!

If you find yourself getting stuck on your Russian or Eastern European ancestry, reach out to Lineages. We’re here to help!

By Dennis

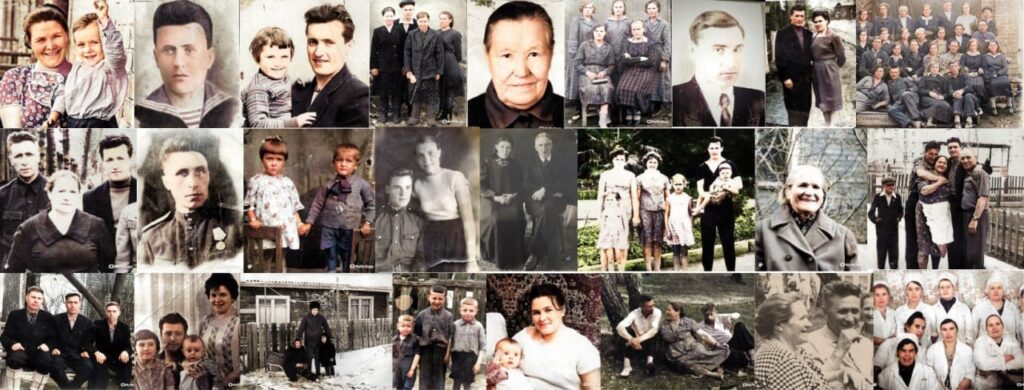

Photos:

- The author.

- Grandparents of the author who lived during Soviet time.

- A photo of a medallion taken while being on expedition with Research Movement.

- A picture taken in the reading-room of the National Historical archive of the Republic of Belarus while working with Catholic records there.

- Photo of the seminar in Tyumen.

- An interview for the media in Novosibirsk.

- Author’s family in immigration in Brazil.