Researching Your Colonial Ancestors, Part II [249 Years of American Independence]

Many Americans today can trace their lineage back to the colonial era and find that their ancestors were from both the northern and southern colonies. Part I of this blog series focused on researching your colonial ancestors from the southern colonies of Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Part II will focus on the northern colonies of Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. Although all parts of the original thirteen colonies, the northern colonies present different opportunities and challenges than the southern colonies.

Town Records

A major difference for research in the northern colonies is the town-based governance. Southern colonies were run by plantations and county governments while the north was run on town meetings. The meeting records were kept in minute books, which offer great detail about land transactions, taxes, voting, apprenticeship and guardianship, and more. If your ancestor lived in the northern colonies, it is crucial to seek the town meeting minutes where they lived. Another great characteristic of northern research is the preservation of records. Unlike southern records, which were oftentimes destroyed by natural disaster or war, northern records have, for the most part, survived the test of time. This creates an opportunity to find a goldmine of information about your northern colonial ancestor.

The minutes were often kept in bound volumes, many of which can be found in the FamilySearch catalog. Religious records can also be found within town meeting records, as civil and religious life often went hand-in-hand. Other places to find town and religious records include state archives, historical societies, town clerk’s offices (though many of these have been digitized, microfilmed, or turned over to an archive or historical society), and AmericanAncestors.org.

Finding The Town

To be successful finding information about your northern colonial ancestor, finding the town where they lived is important. Land and probate records often name the town where the subject was from.

Working backwards from post-colonial ancestors (or individuals who lived through the Revolution) is another way to find a place of origin. Research the children and grandchildren of your colonial ancestor. Check early census records as they often are organized by town. Once you have a town to start with, check for records in and around that town for the records of your colonial era ancestor. Note when towns were founded and check the records of the parent town when necessary.

Published histories of the descendants of colonial-era men and women often name the town where the family first settled. These histories can be found on sites like Google Books, HathiTrust, Internet Archive, in libraries, or by a Google search.

Pro-Tip: As mentioned in part I of this blog post, use FamilySearch’s Full-Text search to help find the town of origin for your ancestor. Use the results only as clues, as it is common to find people with the same name living in different places or perhaps the same place.

Delaware

Delaware was the first state to ratify the Constitution on 7 December 1787 and is the second smallest state in the country. English explorer Henry Hudson explored the Delaware Bay in 1609 which initiated early European settlements in the area. Delaware was governed alongside Pennsylvania until about 1704 when it established its own identity – later dividing into it’s three counties of New Castle, Kent, and Sussex.

Because of its shared governance and disputed borders with Pennsylvania and Maryland, Delaware colonial ancestors may also be found in the records of those colonies, especially in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and Cecil County, Maryland. It is important to check the records of these locations for your Delaware ancestor.

Outside of FamilySearch, some important resources for Delaware research include the Delaware Public Archives, the Delaware Historical Society, Delaware Genealogical Society (which holds indexes for New Castle and Kent County records), and the Swedish Colonial Society. Each of these resources holds many important records such as deeds, probate, court, and church records.

Pennsylvania

Founded in 1681 as a proprietary colony granted to William Penn by King Charles II, Pennsylvania was a haven of religious freedom, especially for the Quakers (or the Religious Society of Friends). Other settlers included the English, Welsh, Scots Irish, Germans, Dutch, and French Huguenots.

Pennsylvania did not have a town-based government system, unlike most of New England. This makes searching at the county level important in successful Pennsylvania research.

Settlers wanting to establish residency in Pennsylvania were required to obtain a land warrant before obtaining a patent. The Pennsylvania State Archives Land Records website includes a searchable index of many of these early land records. There are five main documents created during the process of obtaining land in Pennsylvania:

- Application – This is a request by a potential settler to have a survey completed for the piece of land he is seeking.

- Warrant – This was the document that gave authority for a survey to be completed.

- Survey – A survey was then completed for the prospective piece of land. Described in a metes and bounds system, the land was measured in rods, poles, perches, etc., and natural (trees, rivers, mountains, rocks) or man-made markers (stakes, pointers) were used to describe the boundaries of the land.

- Return – The survey with the description of the land was sent to the Secretary of the Land Office.

- Patent – The final step of the land process and conveyed a clear title and all rights to the owner.

The Quakers kept very detailed records which included births, marriages, deaths, removals (when a person wanted to move to another settlement, this was noted), and disownments. Ancestry has a large collection of Quaker meeting minutes as well as Findmypast.

New Jersey

In 1664, the region of New Jersey (originally part of the Dutch colony of New Netherland) came under English control. The region was split into East Jersey and West Jersey which were separately governed until 1702. Like Pennsylvania, New Jersey did not have a town-based governance.

New Jersey is unique in that many of the county court and land records were not required to be recorded until the 1760s. This creates an issue of a lack of records for the early colonial period. However, alternative records can help substitute for some of these missing records, such as wills and probate, church, and land abstract records. The New Jersey State Archives is a rich resource for mid-Atlantic colonial records.

New York

New Netherland was formed as a Dutch colony in 1624 by the Dutch West India Company and covered the area of present-day New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Connecticut. New York was home to Dutch, English, German, French Huguenot, Jewish, Irish, and enslaved African populations.

Many early records were written in Dutch, English, and sometimes French or German. The influence of Dutch civil law mixed with English common law, creating a unique system for government. Land was often obtained through leases, rather than full ownership.

Slavery was legal in New York, especially in New York City, Albany, and the Hudson Valley. The Dutch Reformed Church sometimes would record baptisms and burials of enslaved individuals, which can be a great resource on top of typical enslavement research (such as bills of sales, inventories, wills, court cases, etc.).

The New York State Archives has a vast collection of genealogical relevant records, such as wills and probate, land records, Dutch colonial records, military records, and court records. The Archives’ website has a name index which can help guide you to specific collections.

Connecticut

English Puritans who migrated from the Massachusetts Bay Colony settled Connecticut in the 1630s. By the 1660s, the colony received a royal charter which gave it self-rule. Connecticut remained Puritan/Independent Congregationalist, and its government was town centralized, which makes town-based research important for learning more about your Connecticut ancestors.

Connecticut has a vast number of early records, especially vital, town meeting minutes, and church registers, and are kept at a town level. To be successful in finding these records for your ancestor, you must locate the town they were from. Many town clerk’s offices maintain the original town books. The Barbour Collection of Connecticut Vital Records is an indexed abstract of many towns’ vital records. Also, the Connecticut State Library holds nearly all town records on microfilm.

Probate records are filed by probate district rather than by town or county. The Connecticut State Library has a guide to probate districts so that researchers can determine where records were filed during specific time periods.

Many genealogies of Connecticut families can be found in published sources, which can be located through repositories like Google Books, HathiTrust, Internet Archive, and libraries. Use this with caution as the information will still need to be verified with documentation.

Rhode Island

After being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for advocating religious freedom and the separation of church and state, Roger Williams founded Rhode Island in 1636. Williams was a Puritan minister who made the colony a haven for religious freedom. It attracted Baptists, Quakers, Jews, Huguenots, and other religions that faced prosecution. In addition, it abolished slavery by law in 1652, making it the first colony to do so. However, it was rarely enforced and was not effective.

Religious records in Rhode Island are scattered or missing because of it having no centralized established church. Start by checking the Rhode Island Historical Society. The historical society has many religious records, but particularly for Baptist and Congregational churches. The Archives of the New England Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends (the Quakers) is housed at the historical society and accessed via the staff and via microfilm in the Reading Room.

New Hampshire

Much of New Hampshire’s growth was after 1700 and it attracted settlers from Massachusetts, Scots Irish, and German immigrants. Counties in the colony were not fully established until the 1760s.

Many early probate records were recorded in Portsmouth, and the after the 1760s they were recorded at a county level. The New Hampshire State Archives holds a large collection of colonial-era probate files. FamilySearch and Ancestry also hold a large collection.

Massachusetts

The Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth in 1620, followed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony by Puritans. In 1691, the two colonies merged into the Province of Massachusetts Bay, which included present-day Maine and New Hampshire.

Massachusetts kept records at the town level and were recorded early on. The most important resource for Massachusetts research is the Massachusetts Vital Records to 1850 (or called the “Tan Books”). These records were taken from town books, church registers, family bibles, and tombstone inscriptions. You will still want to locate the original source to verify the information. A great resource for these records is the New England Historic Genealogical Society which can be accessed online at AmericanAncestors.org.

Although distributed at a town level, land was recorded at the county level beginning in the mid-1600s. FamilySearch has a vast collection of county and town records. Probate began early after the settlement of the colony and can also be found on FamilySearch.

Like the rest of the colonies, many published genealogies and histories can be found online or in libraries. The General Society of Mayflower Descendants is a popular society, and the Silver Books record the genealogies of the descendants of the Mayflower passengers. Connecting to one of the descendant lines will provide you with a jackpot of genealogical information. Once you can confirm you descend from a Mayflower passenger, you can join the society.

Final Thoughts

Each of the thirteen original colonies has its own unique research perks and challenges. Connecting your lineage to the foundation of the United States can be a rewarding experience. Use the tips found in part I and part II of this blog post series to learn more about researching your colonial ancestor. Celebrate America’s independence by researching your colonial ancestor today. If you need help, Lineages is here to assist you!

Tyler

Image Credits:

- Holme, Thomas, -1695, John Harris, and Philip Lea. A mapp of ye improved part of Pensilvania in America, divided into countyes, townships, and lotts. [London: Sold by P. Lea at ye Atlas and Hercules in Cheapside, ?, 1687] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/81692881/.

- Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:American Colonial Village–Old New England and Virginia (NBY 416113).jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:American_Colonial_Village–Old_New_England_and_Virginia_(NBY_416113).jpg&oldid=1051986197 (accessed July 8, 2025).

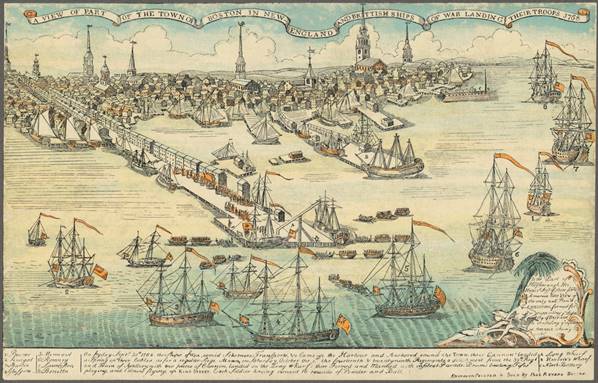

- Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Boston 1768.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Boston_1768.jpg&oldid=927002883 (accessed July 8, 2025).

Resources:

United States Colonial Records – https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/United_States_Colonial_Records

HathiTrust Digital Library – https://www.hathitrust.org/

Full-Text Search – https://www.familysearch.org/search/full-text

Delaware Historical Society – https://dehistory.org/

U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935 – https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2189/

Pennsylvania Land Records Overview – https://www.pa.gov/agencies/phmc/pa-state-archives/research-online/research-guides/land-records-overview.html

New Jersey State Archives Genealogical Holdings – https://www.nj.gov/state/archives/catgenealogy.html

New York State Archives Name Index – https://www.archives.nysed.gov/research/name-indexes-search

Connecticut Barbour Collection – https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1034/

Connecticut Probate District Map – https://libguides.ctstatelibrary.org/ProbateDistrictsByTown

Rhode Island Historical Society – https://www.rihs.org/

New Hampshire State Archives – https://www.sos.nh.gov/archives-and-records-management/archives-and-records-management/archives-and-records-management

Mayflower Society – https://themayflowersociety.org/