The Salem Witch Trials – A Dark Chapter in American History

It’s Halloween time! Americans LOVE this time of year – from the colorful autumn leaves, to pumpkins, hot cocoa, corn mazes, pumpkin spice, and football. But… there’s also a more sinister side, with monsters and witches, haunted houses, paranormal activity, and all manner of ghoulish things! Wherever your imagination takes you, there is plenty of entertainment to satisfy even the most creative among us. And nowhere does it better than Salem, Massachusetts!

Dubbed the Halloween Capital, each year millions flock to this tiny New England village for their spooky attractions, historical places, and fun atmosphere. I recently returned from my first Halloween visit to this quaint little town, and all the rumors are true – IT. IS. CROWDED…and absolutely delightful. The Spirit of Halloween is alive and well, with a myriad of characters dressed in costumes to delight (and frighten) the enchanted tourists.[1]

What made Salem a place that draws millions of visitors each year, particularly at Halloween? That would be the witches. I’m not talking about green faces and wooden broomsticks. I’m talking about REAL WITCHES. Or at least, real ACCUSED witches who were put on trial in 1692 and 1693 – forever re-branding the small, quiet Puritan town of Salem as the place of The Salem Witch Trials.

The trouble began when two young girls, Betty Parris and Abigail Williams, began experiencing strange fits, contortions, and outbursts. The local doctor, unable to find a medical explanation, suggested that the girls might be bewitched. Pressured by the adults around them, the girls accused three women of practicing witchcraft: Tituba, a Caribbean slave; Sarah Good, a homeless woman; and Sarah Osborne, an elderly outcast.

These initial accusations unleashed a wave of fear in Salem and surrounding towns. Puritan society believed that witches could make pacts with the devil, and many feared that dark forces were infiltrating the community. To the deeply religious people of Salem, witchcraft was not only a crime but also a mortal threat to their way of life. Fear, superstition, and religious fervor spread quickly, leading to mass hysteria.

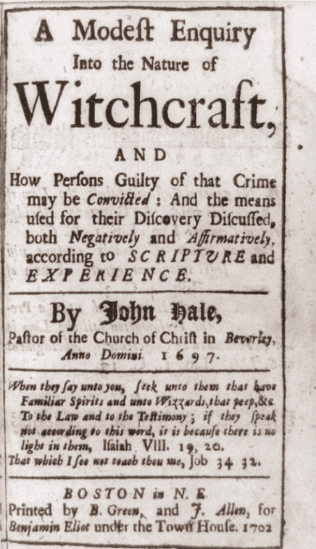

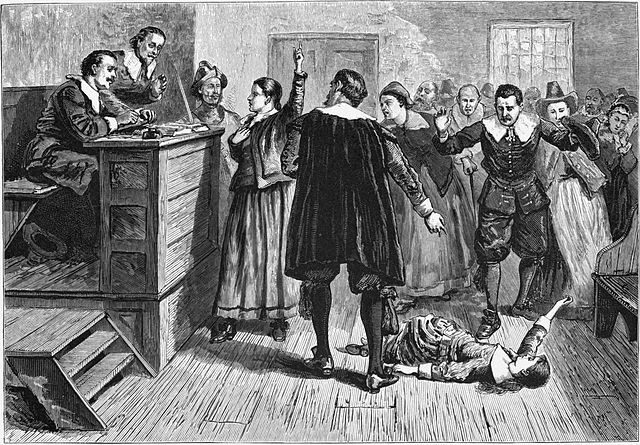

The accusations quickly escalated. Anyone could be accused, and many found themselves on trial for the slightest suspicion. Grudges between neighbors or unusual behavior could lead to someone being named a witch. In a deeply hierarchical society, the trials disproportionately affected women—especially those who were poor, unmarried, or socially marginalized. What made the trials particularly alarming was the use of spectral evidence. This form of evidence relied on witnesses claiming they saw the spirit, or “specter,” of the accused performing witchcraft, even if the accused person had a solid alibi. Despite its unreliability, this evidence was accepted by the court, further fueling the paranoia. Those who confessed to witchcraft were spared from execution, but those who maintained their innocence often met tragic fates. Among them was my 9th great-grandfather, Samuel Wardwell. [2]

Born in 1643 in Boston, Samuel married widow Sarah (Hopper) Hawkes in 1672 in Andover, Massachusetts, and had several children. Shockingly, Samuel Wardwell, his wife Sarah, their daughter Mercy, and Samuel’s step-daughter Sarah Hawks, were all accused of witchcraft and questioned on September 1, 1692. Samuel (age 49) was brought before John Higginson, Esquire, one of the justices of the peace for Essex County.[3] He initially confessed to being entrapped by the devil and afflicting Martha Sprague. “And that he did it by pincheing his coat & buttons when he was discontented, and gave the devil a commission so to doe.”

However, two weeks later he denied his initial confession to the grand inquest, acknowledging that he was fully aware that “he should dye for it: whether: he ownd it or not.” Sure enough, the following day he was found guilty of “Certaine destestable Arts called Witchcraft and Sorceries Wickedly Mallitiously and feloniously hath used practiced & Exercised At and in the Towne of Boxford in the County of Essex in upon and against One Martha Sprague of Boxford, Single Woman, by which said Wicked Acts the said Martha Sprague the day & yeare Aforesaid and divers others days and times both before and after was and is Tortured Aflicted Consumed Pined Wasted and Tormented, and also for sundry other Acts of Witchcraft by the said Samuel Wardell.”[4]

Martha Sprague, only 16 years old, affirmed to the grand inquest that Samuel Wardwell had indeed afflicted her by “pinching & sticking pinse into her & striking her downe.” She testified, “I veryly beleev he is a wizard & that he afflicted me [and others] by acts of witchcrafts.” Others who testified against Samuel were Mary Warin, Mary Walcot, Ephraim Foster, Thomas Chandler, Joseph Ballard, Abigail Martin.

He was hanged on 22 September 1692.

Samuel’s wife Sarah (age 51) was accused of similar dealings, even “tormenting the afflicted p’rsons by loocking on them w’th her Eyes” during the actual trial.[5] She caved under the pressure and confessed that “She thinks She has been in the Snare of the Divel 6 years at w’ch time a man (#theDivel) appeared to her & required her to Worship him.” Additionally, “She was also once at Salem Village Witch metting where their ware many people & that She was Carried upon a pole in Company w’th 3 more,” which she named. She finished by claiming “She is Sorry for w’t She has done & promises to renounce the Divel & all his works & Serve the true Living god.” She was imprisoned, and on January 10, 1693, she was found guilty of “covenanting with the Devill.” She was not hanged, but continued to be imprisoned. It is unknown when she was released.

Mercy Wardwell (age 21) confessed to being insnared by the devil because “people told her that she should Never hath such a Young Man who Loved her.”[6] She thus covenanted “to serve the Divel twenty years & he promised that She should be happy.” She also was said to afflict Martha Sprague and others. Her companions were her father and mother, her (half) sister Sarah Hawks, and William Baker. The trial documents state she owned all the confession “only s’d she did not know her farther & mother ware witches as witness her hand.” She was finally brought to trial on January 10, 1693, pled not guilty, and was found not guilty and discharged, after spending five months in prison. [7]

With Samuel dead, and Sarah imprisoned, on September 26, 1692, the Selectmen of Andover petitioned the court on behalf of Wardwell’s “several small children who are uncapable of provideing for themselves, and are now in a suffering condition: we have thought it necessary and convenient that they should be disposed of in some familyes where they may be due care taken of them.” They were granted permission and 2 days later all the young children were divided up among different families. Poor Sarah – what she must have suffered at this time!

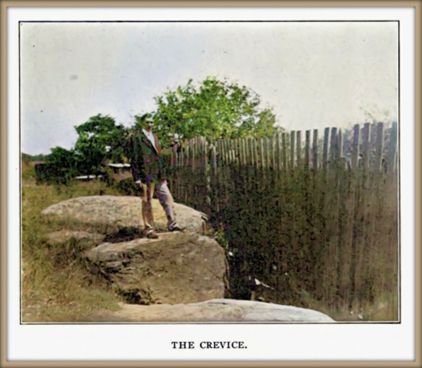

Over the course of the trials, more than 200 people were accused of witchcraft. The court convicted 30 of them, with 19 executed by hanging—14 women and 5 men. Giles Corey, an 81-year-old farmer, suffered a gruesome death by pressing—crushed beneath heavy stones—after he refused to enter a plea. The executions took place on Gallows Hill, a barren place outside Salem Village. [8]

Not long after this, public opinion began to shift. Many influential figures began to doubt the legitimacy of the trials, especially as it became clear that innocent people had been condemned. In May 1693, the governor intervened and pardoned the remaining prisoners. The trials came to an end, but not without leaving deep scars on Salem and the surrounding region.

In the years following the trials, the colony admitted that it had made a grave mistake. In 1697, the Massachusetts General Court declared a day of fasting and repentance, and Judge Samuel Sewall, one of the magistrates who presided over the trials, issued a public apology. By 1711, financial restitution (though far from adequate) was provided to the families who had been wrongly executed or imprisoned. Samuel Wardwell Junior had to petition the court, however, to clear the name of his mother, Sarah Wardwell, because “her name is not inserted in the late Act of the General Court…I thought it my duty to Endeauour that her Name may have the benefit of that Act.” In 1957, Massachusetts formerly passed a bill clearing the names of some of the accused, but it took until 2001 for the last remaining victims to be officially exonerated.

Many of the accused have been memorialized in Salem through monuments, plaques, and museums. Their stories serve as a cautionary tale about the consequences of fear, prejudice, and injustice.

Happy Halloween!

Want to find out if you have ancestors who were involved in the Salem Witch Trials? Reach out to Lineages to help you investigate your spooky past!

Emily

[1] Downtown Salem, Massachusetts, on 19 October 2024 [picture owned by author].

[2] Author Emily Alley pointing to ancestor Samuel Wardwell, hanged as a witch during the Salem Witch Trials, Salem Witch Museum, 18 October 2024 [picture owned by author].

[3] University of Virginia Library, SWP [Salem Witchcraft Papers] No. 133: Samuel Wardwell, Executed, September 22, 1692 (https://salem.lib.virginia.edu/n133.html: accessed 30 October 2024).

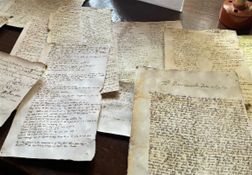

[4] Picture: Copies of legal documents from the Salem Witch Trials, originals at the University of Virginia Library, Salem Witch House, Salem, Massachusetts [picture owned by author].

[5] University of Virginia Library, SWP [Salem Witchcraft Papers] No. 134: Sarah Wardwell (https://salem.lib.virginia.edu/n134.html: accessed 30 October 2024).

[6] University of Virginia Library, SWP [Salem Witchcraft Papers] No. 132: Mercy Wardwell (https://salem.lib.virginia.edu/n132.html#n132.1: accessed 30 October 2024).

[7] Picture: Wikimedia, Witchcraft at Salem Village, unattributed, public domain, The central figure in this 1876 illustration of the courtroom is usually identified as Mary Walcott (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Witchcraft_at_Salem_Village.jpg: accessed 30 October 2024).

[8] Perley, Sidney, 1858-1928. The History of Salem, Massachusetts, vol. 3, pg. 287. Picture of Sidney Perley standing near where the accused were hanged, “with their bodies discarded” in this nearby crevice.

Any pictures or documents not sourced are in public domain