Using Hawaiian Land Commission Awards in Hawaiian Genealogy

We all know the importance of land records in our genealogy research. Deeds can give us key information about our ancestors, like when and where an ancestor lived, how much he purchased his land for, his neighbors, and sometimes even family members. Land records in Hawaii are no different – except Hawaii’s land has a unique history prior to its annexation in 1898.

History

The ancient land system of Hawaii came to an end with the Great Māhele of 1848. Prior to the Great Māhele, all of the lands in Hawaii were owned by the King. The 1840 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii protected the lands of Hawaii and guaranteed that it would belong to the Hawaiian people. King Kamehameha III divided all of the lands in Hawaii into three parts:

- 1/3 Crown lands

- 1/3 Government lands

- 1/3 Konohiki lands, from which Kuleana lands were formed.

The Kuleana Act of 1850 allowed for Hawaiians to make a claim for title on the land that they had lived on and cultivated for years. The Hawaiian Land Commission Awards, established by the King, was a crucial initiative aimed at formalizing land ownership in the Hawaiian Kingdom. These awards were granted to individuals and families who could prove their rightful claims to land, often through a meticulous process of testimony and verification. As a result, these documents provide a treasure trove of information for genealogists, offering insights into familial connections, migrations, and cultural heritage.

Delving into Land Commission Awards can be a game-changer. These documents not only outline land ownership but also include personal narratives, relationships, and ancestral ties. By examining the awarded lands and the individuals associated with them, genealogists can piece together a comprehensive picture of their family history, tracing lineages through generations.

What Can You Discover?

Hawaiian Land Commission Awards are rich sources of information that can unlock a wealth of details about individuals, families, and the historical context of land ownership in Hawaii. Here are some key discoveries that genealogists and researchers can make when exploring these awards:

Ancestral Connections:

- Land Commission Awards often include information about individuals who were granted land, providing details about their family relationships, including parents, siblings, and spouses.

- Examining multiple awards associated with the same family can help trace ancestral connections over several generations.

Land Descriptions:

- Land Commission Awards include detailed descriptions of the granted lands. This information can be valuable for understanding the physical environment in which ancestors lived, worked, and cultivated their livelihoods.

Witness Testimonies:

- Witnesses played a crucial role in the land award process, providing testimonies that supported or contested claims. These testimonies may offer additional details about individuals, relationships, and events in the lives of those seeking land.

Succession of Land Ownership

- Some land awards may include information about the transfer of land ownership within a family. This succession data can help create a timeline of property ownership and changes over generations.

The Application Process

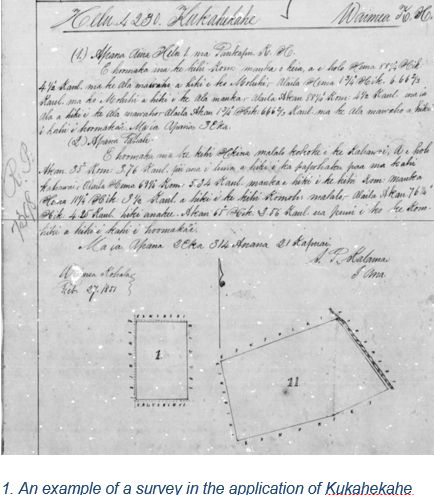

Like many kinds of land grants in the United States, Hawaiians went through an application process in order to gain title to their land. The series of steps started with a person making a claim to the land. This included having two witnesses testify that the person lived on the land, having the land surveyed, and finally, having the application approved and title awarded.

Step One – Applicant Makes a Claim

A person wanting to gain title to their land would file an application with the land commission. In the application testimony, the applicant would state their name, where they lived, the land they were claiming, and they almost always list how long they have lived on the land and who they received the land from. Sometimes the applicant received the land from their parents or other family members, who could be named in the application.

Step Two – Two Witnesses Needed

All applicants were required to have two people testify that the information the applicant is claiming is true. These could be friends, family members, or people who knew the applicant and knew how long they lived on the land and who they received the land from.

Step Three – Land Commission Award (LCA)

After the land commission approved the claim, a survey was ordered for the land. This gave the land a legal description and recorded the bounds and acreage of the land. Sometimes applicants had multiple parcels of land. Each parcel of land was called an “ʻāpana”. You may see ʻāpana 1, ʻāpana 2, etc. on the survey when there is more than one parcel. The approved LCA was then given an LCA number.

Step Four – Royal Patent Granted (RP)

The final step in the land process is the issuance of the Royal Patent (RP). This awarded title to the applicant, and gave him the right to do as he pleases with the land. The application was then given a Royal Patent number. Some applicants kept the land for a long period of time, and others sold it shortly after.

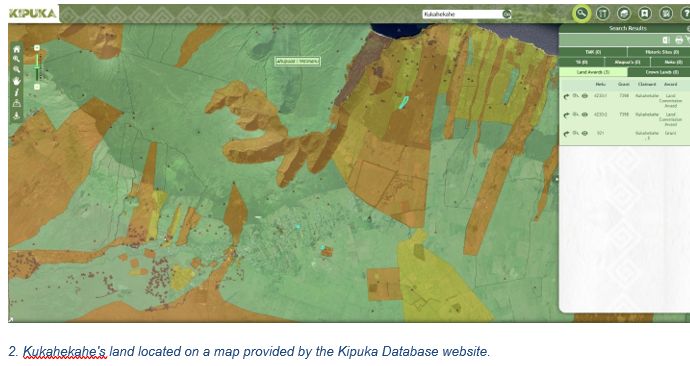

Locating the Records

There are a few places where researchers can find these documents. The most accessible resource is Kipuka Database (kipukadatabase.com). In addition to providing the application packet (which includes the initial application, witness testimonies, land commission award, and royal patent), Kipuka Database also plots out the bounds of the parcels on a modern day map. This will allow you to locate the land. You can also click on surrounding parcels to see who your ancestor’s neighbors were.

Understanding the Records

Most of the records are written in Ōlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language), but translations can be found. One great resource for free translations for these documents can be found at Ava Konohiki (avakonohiki.weebly.com). You can go to the website to view a tutorial on how to locate the translated documents.

Next Steps

After you locate your ancestor’s land application, fully transcribe all of the documents so that you can extract all of the information. Make note of the witnesses and neighbors – these could be family members. Also make note of the Land Commission Award and Royal Patent numbers.

Be sure to find out what happened to the land. Did your ancestor live on the land for the rest of their life? Probate records will often list the Royal Patent numbers if the ancestor was still in possession of the land at the time of their death. Also be sure to check deeds, as many awardees sold their land, sometimes to family members. Heirs of deceased awardees also made note of the relationship to the awardee. This can connect generations of families in one document.

Have fun discovering the land your ancestor loved and lived on!

By Tyler

Resources

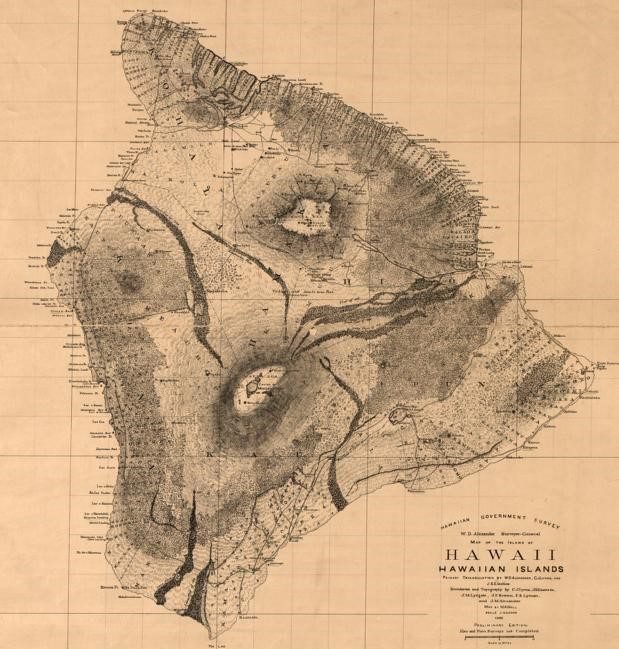

Map of Hawaii, Hawaiian Islands in public domain Wall, W. A.; Hawaii. Oihana Ana Aina Aupuni, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/hawaiilandtenureresearch/mahelerecords