Valentine’s Day

Ahh…Valentine’s Day. Love is in the air. Romantic gestures are everywhere, as are expressions of love between friends, parents to children, and between family members. The Illustrated London News on 11 February 1871 called it “silly season.” I get that some people hate the commercialism of this holiday, but I find it lots of fun! After a bleak January, the stores come alive with flowers (roses, mostly), chocolates, candies, greeting cards, stuffed animals, and hearts galore!

But Valentine’s Day wasn’t always commercialized. In fact, it’s only been this way for roughly the last 175 years, which might sound like a long time, until considering that the holiday has been around a LOT longer than that. In fact, almost 1,800 years!

History of Valentine’s Day

Valentine’s Day has a long and complex history, blending ancient Roman traditions, Christian martyr stories, and later European customs into the holiday we know today.

The origins of the holiday can be traced back to Lupercalia, a Roman pagan festival celebrated from February 13 to 15. It was a fertility festival dedicated to Faunus (the Roman god of agriculture) and Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome. During the festival, men sacrificed animals and whipped women with animal hides, believing it promoted fertility. Unmarried men and women would randomly be paired for courtship, sometimes leading to marriage.

Christian Martyrs[1]

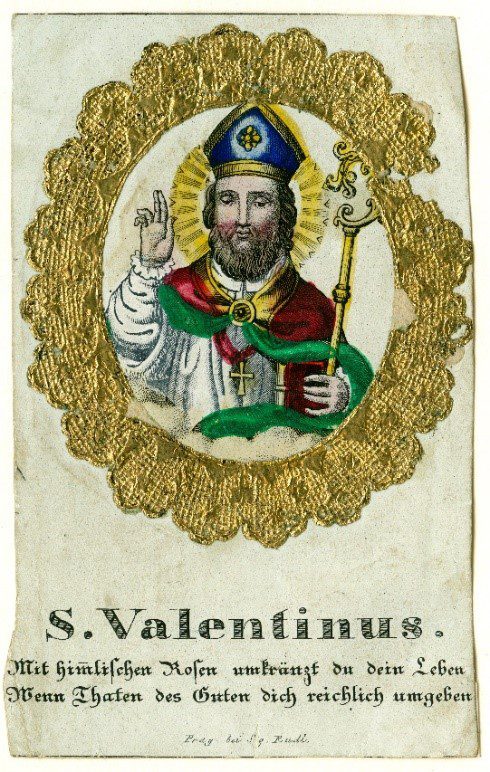

Then we have the Christian martyrs. The Catholic Church recognizes at least three different saints named Valentine or Valentinus, all martyred. One legend states that St. Valentine of Rome, a priest in the 3rd century, defied Emperor Claudius II, who had banned young men from marrying (believing they made better soldiers). Valentine secretly married couples and was executed on February 14, around 269 AD. Another story claims Valentine was imprisoned for helping persecuted Christians. Before his death, he allegedly sent a letter signed “From Your Valentine” to his jailer’s daughter, whom he had befriended. In all likelihood, there are many origins of Valentine’s Day that aided in the establishment of the holiday.

Medieval Romance

By the 14th and 15th centuries, Valentine’s Day became linked with romantic love, thanks to poets like Geoffrey Chaucer. In “Parliament of Fowls” (1382), Chaucer wrote about birds choosing their mates on St. Valentine’s Day. “For this was sent on Seynt Valentyne’s day / When every foul cometh ther to choose his mate,” reinforcing the idea of courtly love.[2] By the 16th and 17th centuries, exchanging love notes on February 14 became popular in England and France.

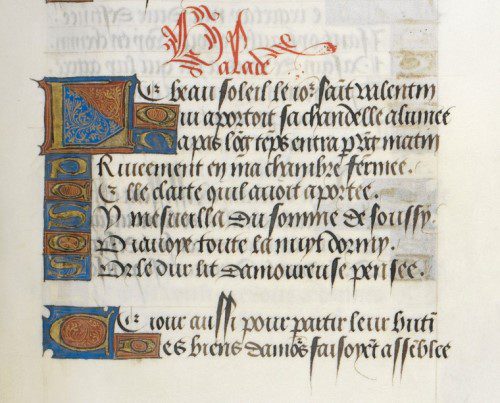

The oldest known Valentine is often erroneously attributed to Charles, Duke of Orleans, in 1415, when he was imprisoned in the Tower of London. While this particular claim is unsubstantiated, Charles d’Orleans was an important figure in the development of Valentine’s Day. According to the British Library, about fourteen of his poems are about Valentine’s Day. One such poem was written after the death of his partner in 1430/35. He tells how he wakes up and hears the birds singing and choosing the mates, referencing Chaucer’s “Parliament of Fowls.” Charles laments:

Saint Valentin choisissent ceste annee

Ceulx et celles de l’amoureux party.

Seul me tendray, de confort desgarny,

Sur le dur lit d’ennuieuse pensee.

(Let men and women of Love’s party

Choose their St. Valentine this year!

I remain alone, comfort stolen from me

On the hard bed of painful thought).[3]

In truth, the earliest known surviving Valentine is from 1477 between lovers Margery Brews and her soon-to-be husband John Paston, a member of the Norfolk aristocracy. They exchanged many love letters in the year leading up to their marriage (part of the Paston Letters collection). According to the British Library, “In one particular letter, sent in February, Margery described John as her ‘right well-beloved Valentine’ and signed off the letter as ‘your Valentine, Margery Brews.’”[4]

Modern Romance

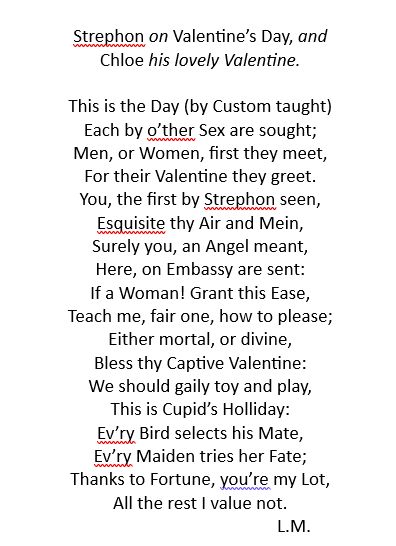

The holiday was mostly celebrated through love-notes and poems, and certainly was not commercialized, before the 19th century. There is almost no mention of Valentine or Valentines in the British Newspapers Archive between 1700 and 1799, aside from mentioning it as a holiday. Often, the references come in the form of poems, such as this one published in 1765 in the Bath Chronical and Weekly Gazette:[5]

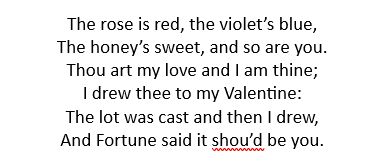

The most popular Valentine’s Day poem was published in Gammer Gurton’s Garland in 1784:[6]

Books were published for the purpose of helping young men compose sentimental verses of poems to their lovers, such as The Young Man’s Valentine Writer, published in 1797. The following reference to such books was published on 21 February 1791 in the Hampshire Chronicle:[7]

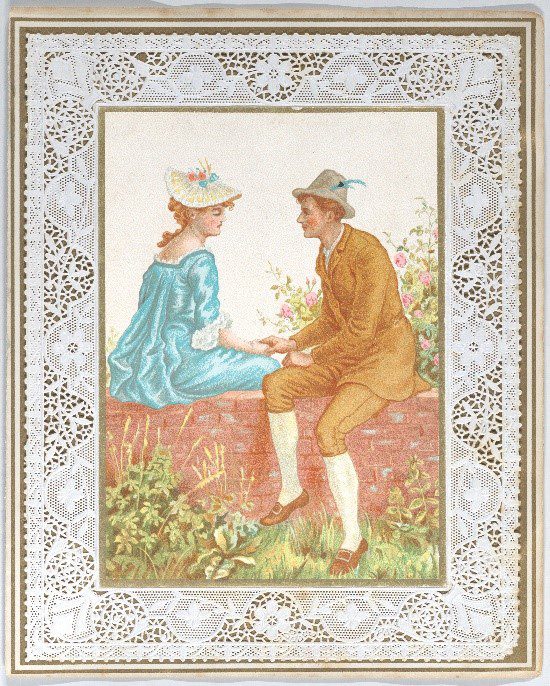

By the mid-1800s, British newspapers were filled with Valentine’s advertisements: “Just received direct from London, upwards of 5000 of the choices and NEWEST DESIGNED VALENTINES, superior to anything of the sort yet produced, at very reduced prices.”[8] Traditionally a holiday celebrated by aristocrats, who could afford such luxuries, it soon became fashionable for the middle classes (merchants, tradesmen, and professionals) to emulate the better-off. [9]

And this popularity eventually spread to the United States, who appreciated the middle-class values of “romantic love, sentimentalism, and fashion.”[10] Before the 1840s, Valentine’s Day was largely forgotten in the United States; just one of many medieval saints’ days that went unobserved. But the rise of influential advertising companies revitalized the holiday by creating consumer demand.[11] Traditionally involving only young men and women, the holiday definition expanded to include any and all ages. Merchants even created “juvenile valentines” to include children in the festivities. In the 1840s, Esther Howland of Worcester, Massachusetts, known as the “Mother of the American Valentine,” began mass-producing romantic greeting cards, replacing the traditional hand-made cards. “In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the word ‘valentine’ meant a person or a relationship. However, in the nineteenth century, the word came to mean an object of exchange.”[12]

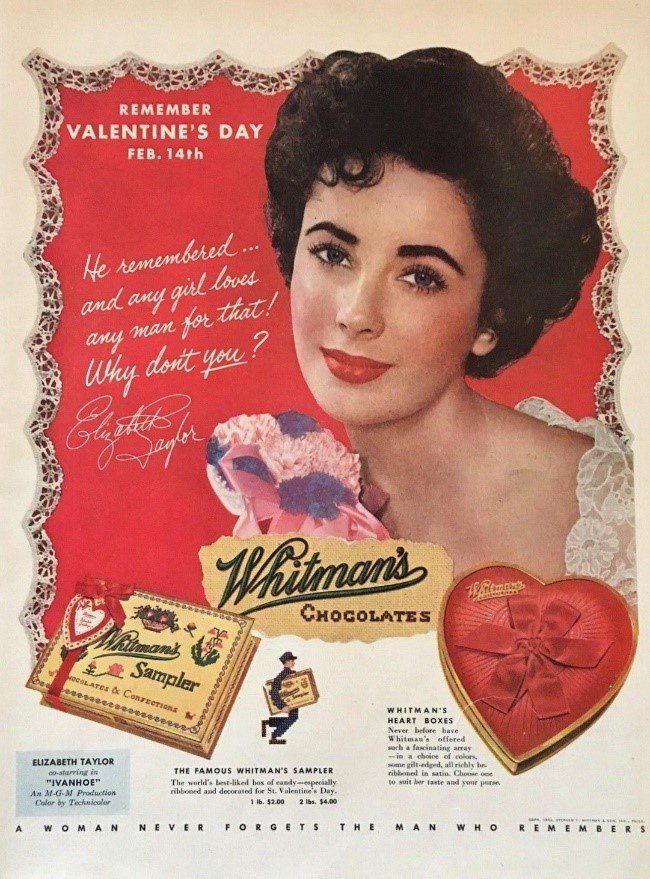

By the 20th century, technology made the printing of valentine’s cards in color and with various textures even more inexpensive. Advertising had expanded to things like chocolates and flowers.[13] Children started exchanging candies and cards in school. The holiday has expanded beyond the British Isles and the United States and now is celebrated in many parts of the world, although often to a lesser degree.

In our modern day, the use of social media has further expanded the variety of ways people celebrate the holiday, with “Galentine’s Day,” “Single Awareness Day,” or celebrating your pets. Some choose not to celebrate it at all. Gone are the days where a Valentine was a sign of a betrothal or serious romantic relationship. Now, it is mostly about spreading the love!

How did your parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents celebrate Valentine’s Day? Do you have old Valentine’s cards or love letters that have been preserved and passed down? If so, consider digitizing them and adding them to Memories on FamilySearch or in your gallery on Ancestry so others can enjoy seeing the romance of their progenitors!

However you will be spending this February 14th, we want to wish you a very Happy Valentine’s Day!

If you want to learn more about your own family history, and perhaps even a love story or two, reach out to Lineages and let’s get started today!

Emily

All images are in the public domain.

[1] Wikimedia Commons, “St Valentine, colored – Pray for us,” by Sigmund Rudl (Prague), date unknown (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MCC-42865_H._Valentinus,_ingekleurd_-_Bid_voor_ons_(1).tif: accessed 12 February 2025. “It may look like a Valentine’s card, but this is a devotional card. These types of cards contain, for example, biblical scenes and images of saints. The Catholic Church distributes them in large quantities. This is to stimulate religious experience and the veneration of saints in daily life. The cards, with colorful pictures and prayers for special favors, are designed for the widest possible audience.”

[2] History.com, History of Valentine’s Day, 22 December 2009 (https://www.history.com/topics/valentines-day/history-of-valentines-day-2: accessed 12 February 2025).

[3] The British Library, Medieval manuscripts blog: Charles d’Olreans, earliest known Valentine?, 14 February 2021 (https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2021/02/charles-dorl%C3%A9ans.html: accessed 12 February 2025).

[4] The British Library, Medieval manuscripts blog: My ‘right well-beloved Valentine,’ 14 February 2019 (https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2019/02/my-right-well-beloved-valentine-.html: accessed 12 February 2025).

[5] The British Newspaper Archives, Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, Thursday, 7 March 1765 (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000211/17650307/013/0001: accessed 13 February 2025).

[6] Wikipedia, “Valentine’s Day” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valentine%27s_Day: accessed 13 February 2025).

[7] The British Newspaper Archive, Hampshire Chronicle, Monday 21 February 1791 (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000230/17910221/017/0004: accessed 13 February 2025).

[8] The British Newspapers Archive, Westmeath Independent, Saturday, 12 February 1848 (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001285/18480212/008/0001: accessed 13 February 2025).

[9] Wikimedia Commons, “Valentine Met DP885968,” Artist: Kate Greenaway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1876 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Valentine_Met_DP885968.jpg: accessed 13 February 2025).

[10] Natalie Van Dyk, “The Reconceptualization of Valentine’s Day in the United States: Valentine’s Day as a Phenomenon of Popular Culture,” (Wilfrid Laurier University, 2013), vol 1, issue 1, article 4 (chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=bridges_contemporary_connections: accessed 12 February 2025).

[11] Natalie Van Dyk, “The Reconceptualization of Valentine’s Day in the United States: Valentine’s Day as a Phenomenon of Popular Culture,” (Wilfrid Laurier University, 2013), vol 1, issue 1, article 4 (chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=bridges_contemporary_connections: accessed 12 February 2025).

[12] Natalie Van Dyk, “The Reconceptualization of Valentine’s Day in the United States: Valentine’s Day as a Phenomenon of Popular Culture,” (Wilfrid Laurier University, 2013), vol 1, issue 1, article 4 (chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=bridges_contemporary_connections: accessed 12 February 2025).

[13] Wikimedia Commons, “Remember Valentine’s Day – Elizabeth Taylor – Whitman’s Chocolate, 1952” (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Remember_Valentine%27s_Day_1952_-_Elizabeth_Taylor_-_Whitman%27s_Chocolates.jpg: accessed 12 February 2025).