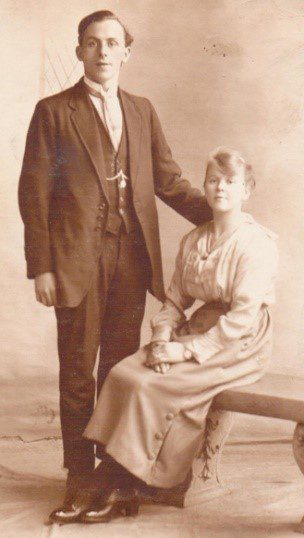

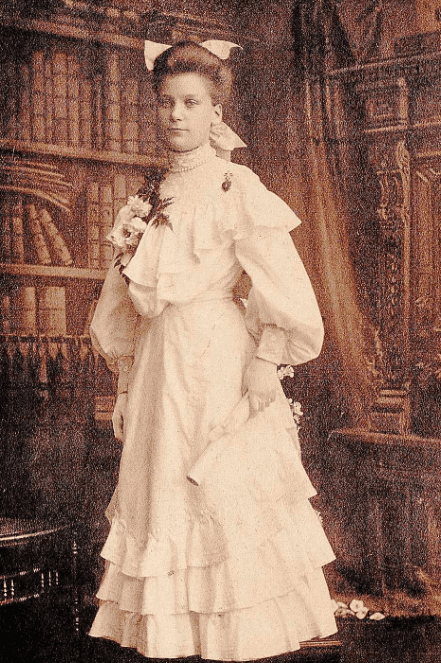

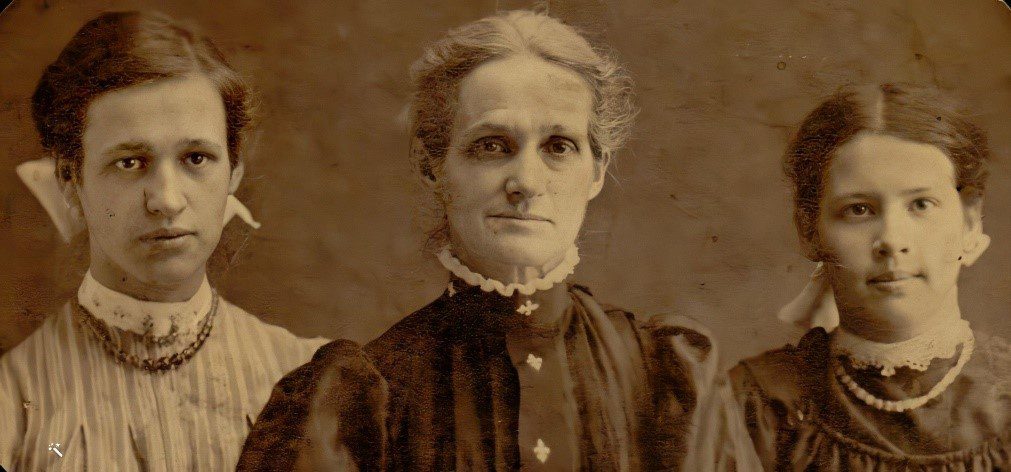

Women’s History Month: Finding Your Female Ancestors

While acknowledging the vast contributions of women throughout history, it can often be a challenge discovering exactly who these women were, to whom we owe so much. Historically, records pertaining to women—particularly married women—were limited or nonexistent, largely due to the legal and societal constraints placed on them. In Colonial America, a woman’s legal identity was often absorbed into that of her husband upon marriage, stripping her of individual rights and autonomy. As a result, researchers frequently need to trace female ancestors through the men in their lives—fathers, husbands, brothers, or sons.

This article will explore the variety of ways to unearth and discover our female ancestors.

Marriage Records. While an important and useful record, these records can be difficult to locate, especially if the couple did not live near each other. Start your search in the towns, churches, or counties where either individual resided. If no records are found, expand your search to adjacent jurisdictions. Marriages often took place in the bride’s hometown or local church, which may have been some distance from the groom’s residence, complicating the search. If the record cannot be found, try locating a marriage announcement in newspaper archives. As you research, consider key questions: How old were the bride and groom when they married? Was this a legal age to be married at the time? When was their first child born? While nine months after marriage is a common estimate, this timeline can vary. Although less frequent, divorce records can be a valuable source of insight, often containing personal and legal details not found elsewhere.

Church Records. Begin by searching for christening or baptism dates in parish registers or local churches where your ancestors lived. Burial records may also be available and can provide key information. Historically, women were often active members of their church communities, which increases the likelihood of finding their names in various records. Meeting minutes, newspaper articles about church events, and listings of women’s groups, charities, or fundraisers may mention them by name. Additionally, women frequently appeared in church records as witnesses to baptisms and marriages—offering further opportunities to uncover familial connections.[1]

Census Records. Be sure to examine every available census that spans your ancestress’s lifetime, as each one may reveal new details. Pay close attention to nearby households, as extended family members often lived in close proximity. Census records kept after 1850 include everyone in the household, their location, birth place, their age, county, race, gender, marital status and year of marriage. These details can offer valuable insights into a family’s structure, movements, and circumstances at specific points in time. Beyond basic personal data, census records help establish relationships, trace generational patterns, and fill in gaps where other records may be lacking.

Land Records. As Marylynn Salmon explains, “Under the common law, women and men gained certain rights and responsibilities after marriage. No longer acting simply as individuals, together they constituted a special kind of legal partnership, one in which the woman’s role was secondary to the man’s…” Salmon’s detailed description highlights how marriage significantly limited a woman’s legal and financial independence. Once married, a woman could not file or participate in legal actions without her husband, and all her personal property—such as wages, jewelry, or investments—came under his control. He made all managerial decisions concerning her lands and tenements and controlled the rents and profits. Although husbands managed their wives’ real property, they were not legally allowed to sell or mortgage it without the wife’s consent, though determining what constituted “free” consent was often contentious in court.[2]

Understanding the legal limitations placed on women during the period and region being researched can help explain the scarcity of records tied directly to them. Despite these constraints, land deeds can still be a valuable resource. Married couples often appear together in such documents, offering potential clues about a woman’s identity and presence within the historical record.

Court Records. Gathering as much information as possible about a woman’s husband and his family can provide valuable leads. Civil court records may reveal disputes over estates, legal proceedings, or property matters that name both husband and wife. Broaden your search by exploring local archives for clues such as which pew they used in the local church. Who were their neighbors? Did they stay in one area or did they move around frequently? What was the husband’s occupation? In what social circles did they move? What was their socioeconomic standing? Were they financially stable or did they struggle?

Town meeting minutes, selectmen’s records, and court testimonies can all offer context about a family’s role in the community. Additionally, understanding the family’s ethnic or cultural background may provide further insights. For instance, some Irish and Scottish families followed traditional naming patterns, and women in these communities were more likely to retain their maiden names—offering an important clue for tracing female lines.

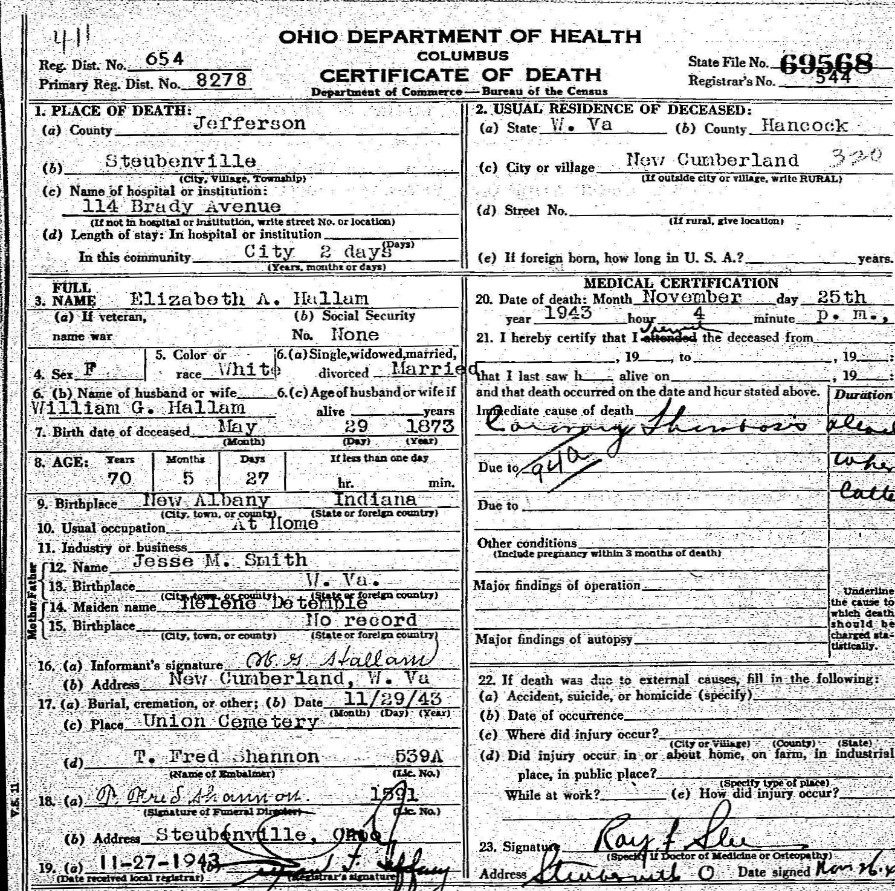

Death and Probate Records. A husband’s death record may name his wife, offering a direct connection. If she remarried, tracing her new married name can open up additional leads. Gravestones, cemetery records, and obituaries can also provide valuable details—often revealing a woman’s maiden name through references to her parents or siblings. Be sure to search newspaper indexes for obituaries not only of the woman herself, but also of her children, siblings, or spouse, as these may contain identifying information.

Wills are especially informative. Widows and their children are frequently named in a husband’s will, while the wills of a woman’s parents may include her name—sometimes with both maiden and married surnames. Even in cases where no will exists, estate settlements can be revealing. Daughters were often listed under their married names, so analyzing these documents closely may help uncover maternal connections.

Additionally, death and birth records from the next generation can be useful. Children’s death certificates, for instance, often include the names of both parents, which can lead to the discovery of a missing maiden name.

Tax Records. These documents can offer important clues—especially in identifying women who may have owned property within a household. As one researcher noted, “These records may also provide clues to the name of the widow of a landowner for the year or two after the death of the husband, along with a description of the property and, for early tax lists, the name of the person who originally was granted the patent.”[3] Investigating that original land grant recipient may reveal whether the property came through the woman’s side of the family, such as a parent or grandparent.

Directories. These records often include both single and married women, particularly those listed prior to marriage or shortly after becoming widowed.[4] In many cases, directories provide additional details such as occupations, places of employment, and residential addresses. Take note of the address of the household. Seek which households housed an independent woman and find where single women may be living.

County Histories. These publications may include Revolutionary War rolls or registries listing the families of those who served or died in the war—offering valuable leads. Women can be mentioned in biographies about their fathers, husbands, brothers, uncles, and sons. Women who were actively involved in their communities may be mentioned in these histories. They also could be mentioned if they were the first white residents in the particular town, or a first marriage, or the first child born in a new town.[5]

Books, Indexes, and Bible Records. Books and indexes available through platforms such as FamilySearch, Ancestry, Findmypast, MyHeritage, and the New England Historic Genealogical Society contain billions of names that may help identify women’s maiden names. It is important to seek vital records published in book form that have not yet been digitized. For example, deed books may contain entries where a widow formally relinquished her dower rights—offering a valuable clue to her identity and marital status.

One particularly rich source of family history is the family Bible, which was often one of the few printed books early colonists brought with them to the New World. These Bibles were treasured heirlooms, commonly used to record births, marriages, and deaths across generations. “A family Bible was and still is an officially recognized document that could be used in a court of law as proof of a person’s age, birth, marriage or death.”[6] The family Bible was often passed down through a female line. It could contain notes, newspaper clippings, letters and other memorabilia that can shed light on the family or the female ancestors who may have had possession of the Bible.”[7]

Conclusion. Women have always played a vital role in shaping families, communities, and entire nations—yet their stories are often hidden in the shadows of history. Taking the time to research and understand our female ancestors brings their experiences to light and gives voice to those who were frequently left out of official records. As Sharon Carmack said, “As you can see, women no longer have to be kept in obscurity in a family history. If you thought you’d done all you could in researching and writing about your female ancestors, think again. Remember, half of all of your ancestors were women, and most are waiting silently for you to tell their life stories. Don’t let their legacy be just a name on a chart.” [8] By exploring the sources outlined above—and with a bit of patience and determination—you may uncover a maiden name, a forgotten story, or a rich legacy just waiting to be rediscovered.

Lineages has decades of experience locating illusive female ancestors. Reach out to us today – we’d love to help you discover your own important family stories.

Jessica

[1] Dawne Slater-Putt, “Hunting for Your Female Ancestors,” Heritage Quest, 17:3 (May/June 2001), p 21.

[2] Marilynn Salmon, “Women and the Law of Property in Early America”, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986) p 14-15.

[3] Roseanne R. Hogan, “Female Ancestry,” Ancestry, 12:2 (March/April 1994) p 27

[4] Dawn Slater-Putt “Hunting for Your Female Ancestors,” Heritage Quest17:3 (May/June 2001), p 20-21:

[5] Slater-Putt p 21

[6] William Dollarhide, “Identifying Female Ancestors: Some Case Histories,” Heritage Quest; 17:3,(May/June 2001), p 14-15

[7] Slater-Putt p 23

[8] Sharon DeBartolo Carmack, “Mystery Women,” Family Tree Magazine,” Vol no, Issue Number (April 2001), p24

Photos and images are in possession of Diane Rogers